1. the architecture of inhabitation:

transgressing the boundaries of formal architecture

2021

m. arch. dissertation

This dissertation challenges the notion that architecture can ever be complete, shifting the conversation

from ‘architecture as product’ to ‘architecture as process’ and effectively accepting that architecture is subject

to change.

The inhabitant can act as this force of change over the course of the building’s lifetime, making

it ‘living’ architecture.

Unfortunately, formal or conventional architecture tends to forget this, negating the

dweller’s inhabitation and agency as a valid contribution to architecture. Instead, it perceives the dweller as

a contingency, reducing the creative inhabitant to a generic user in an attempt to create a false sense of

stability and completion.

However, inhabitation and dweller agency produce their own architecture: the architecture of inhabitation.

If to inhabit is to create and to contribute by means of this agency, then to inhabit is inevitably to transgress

the boundaries of formal architecture.

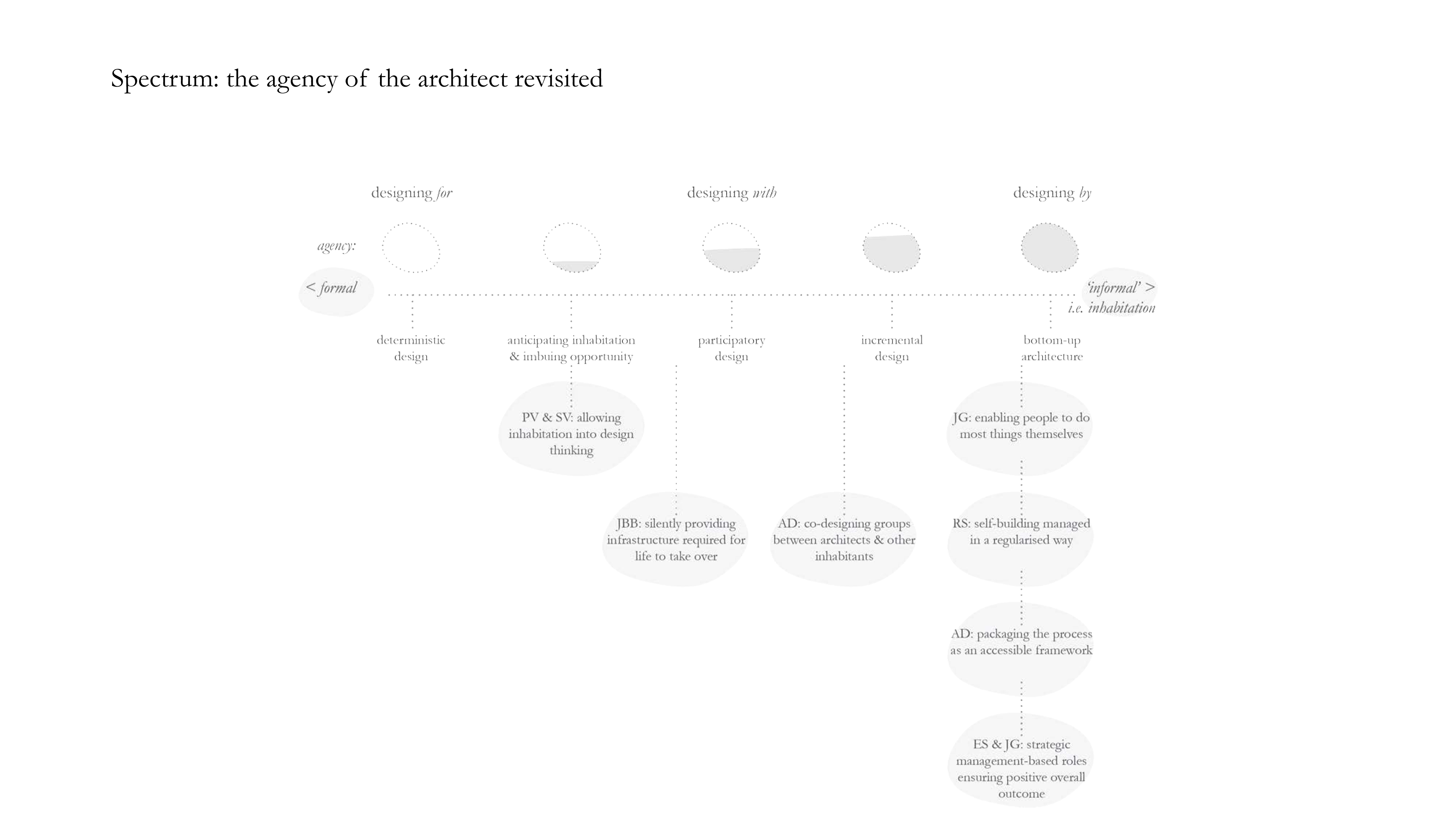

While designing with people rather than for people is a step in the right direction, it is imperative that we seek ways to facilitate designing by people.

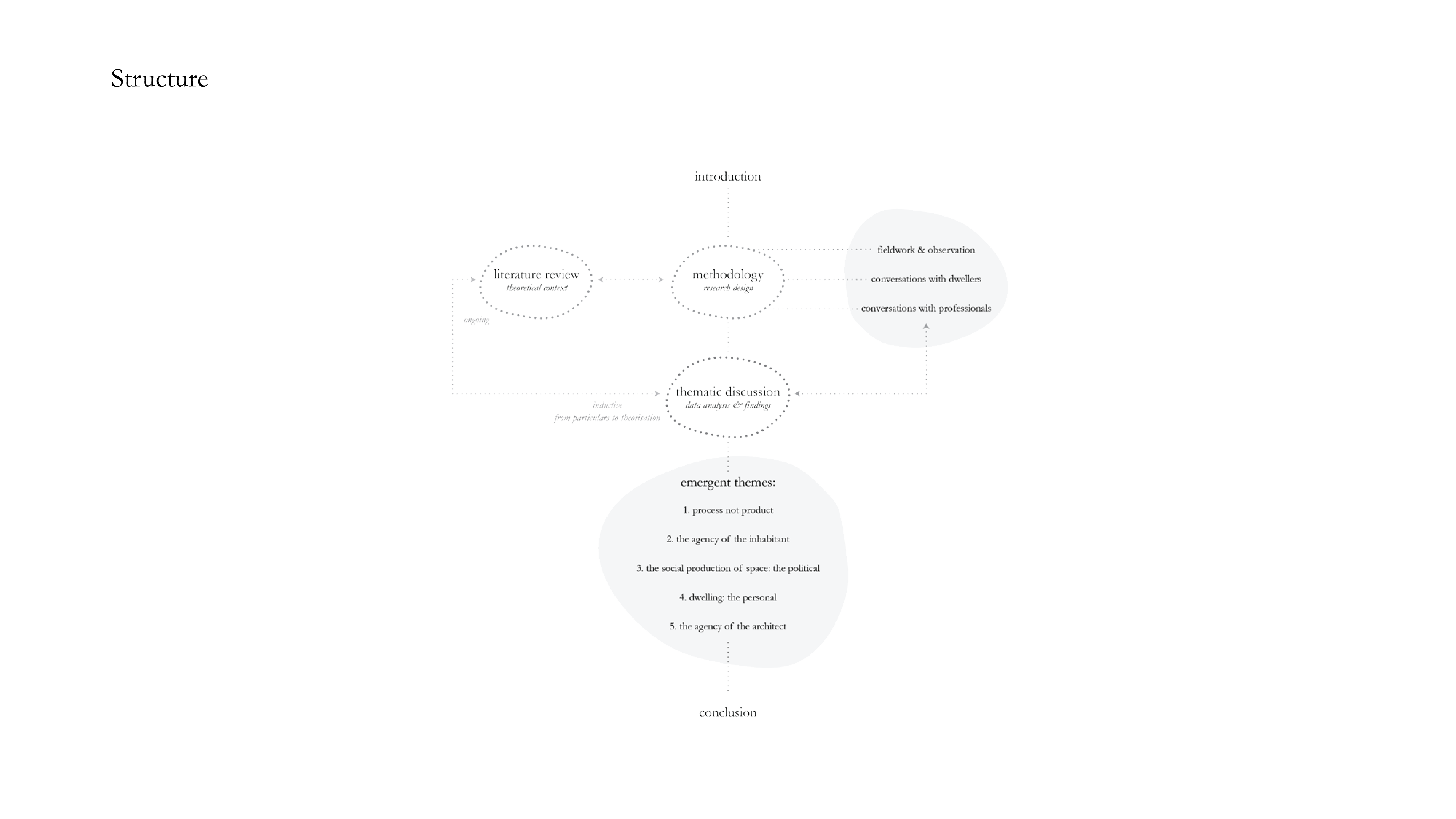

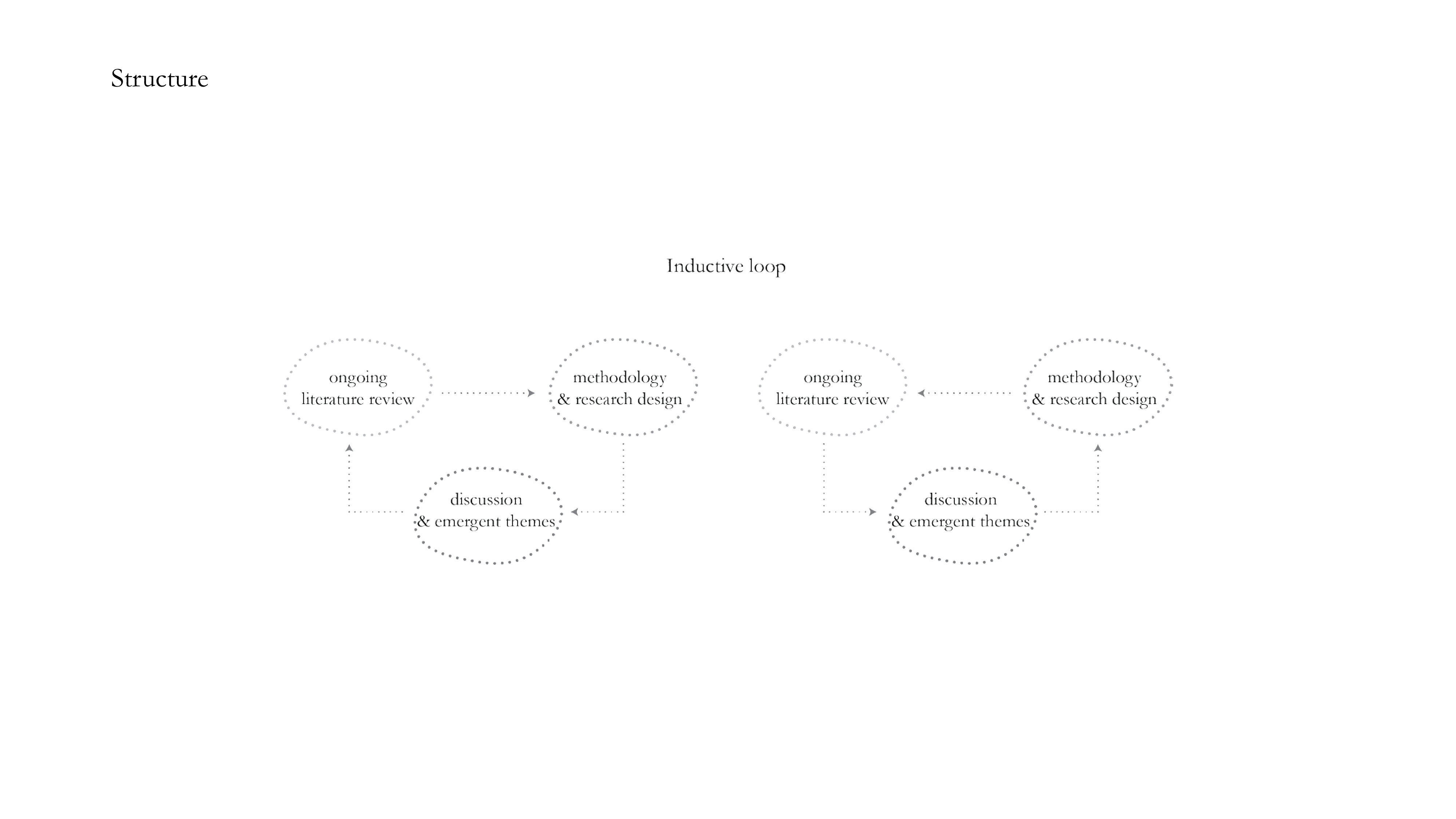

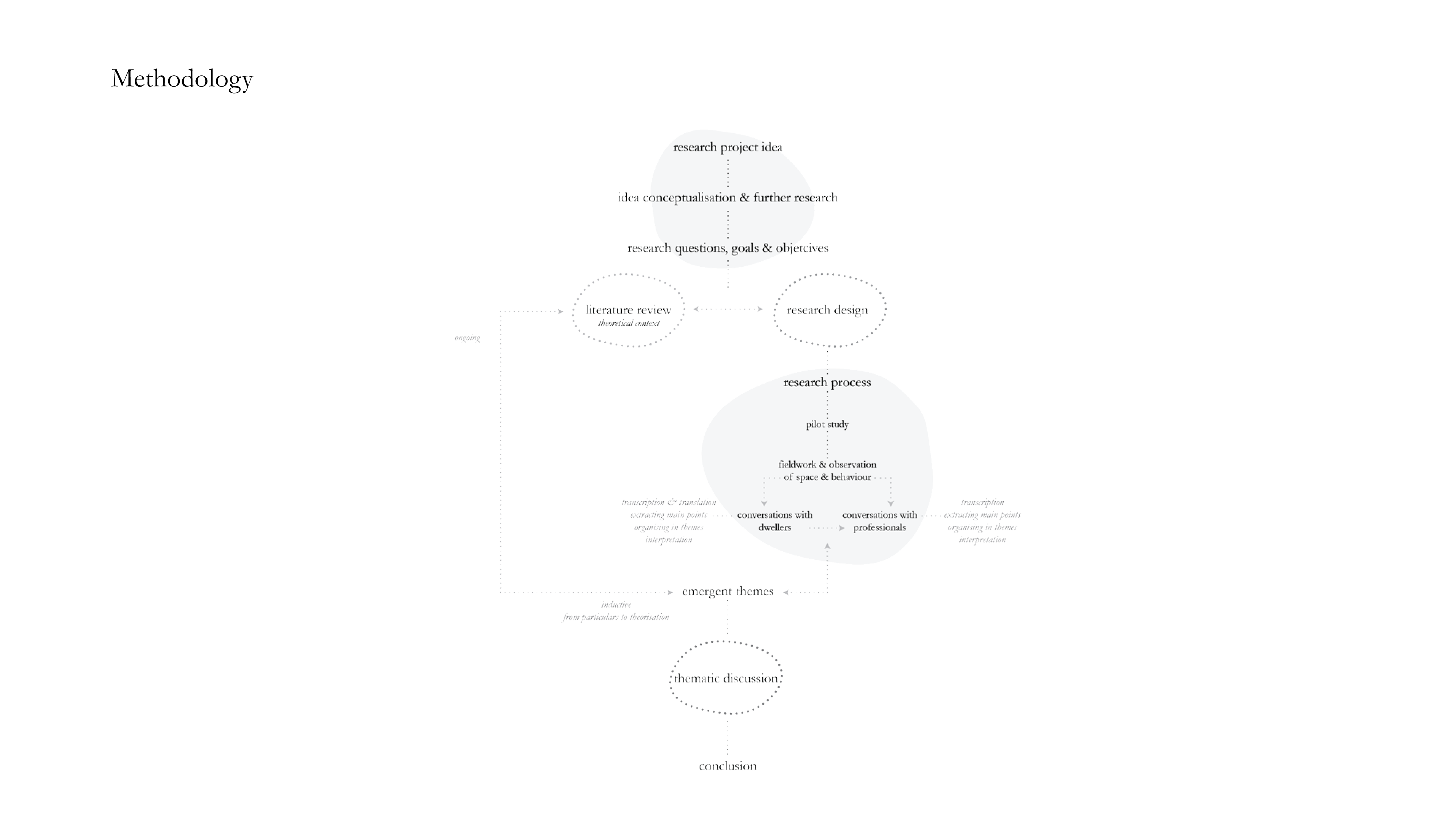

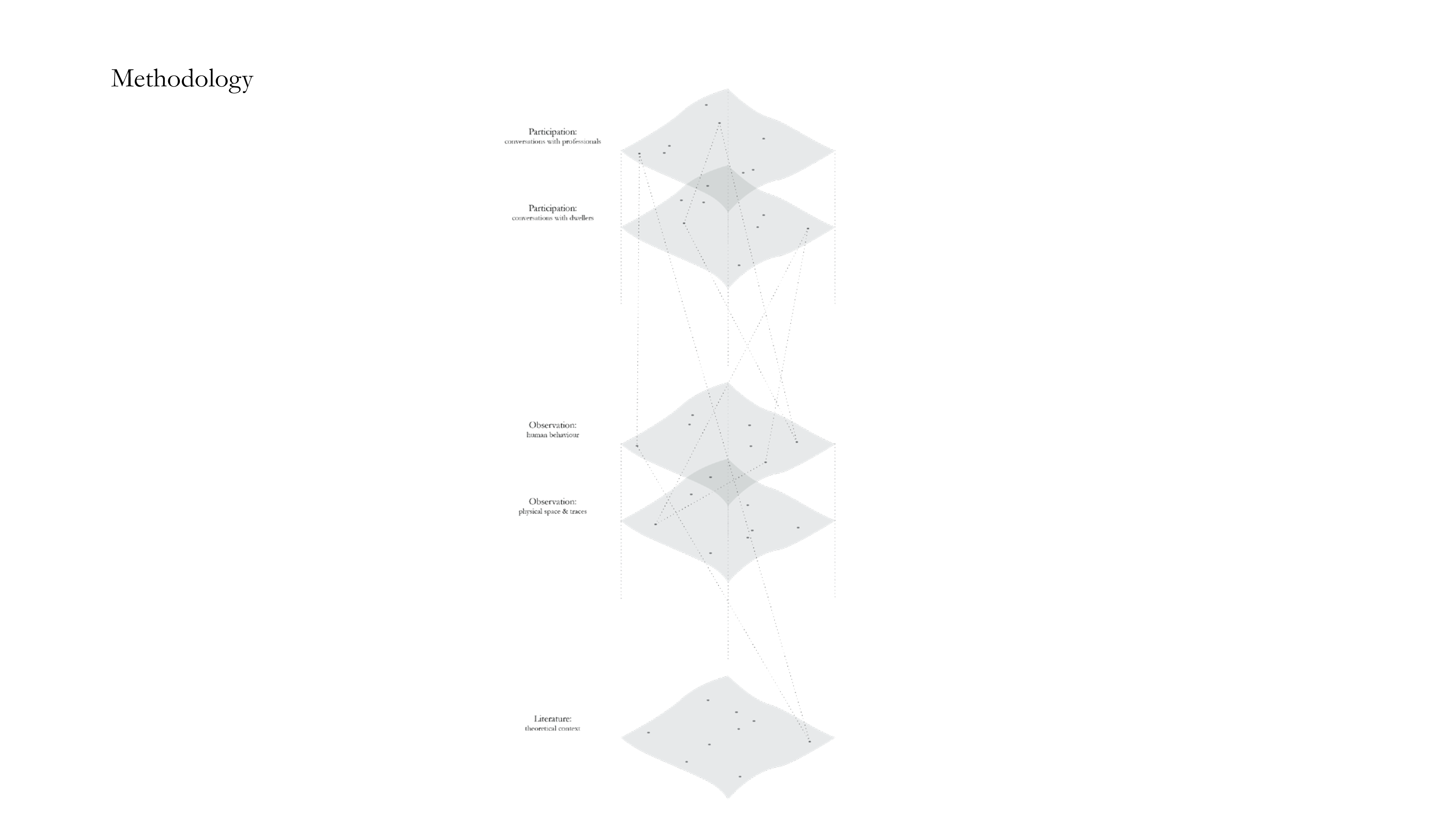

In emphasising process over product, the dissertation itself is very process-driven. Structured in an inductive manner, different parts of the study continuously loop and feed into each other reciprocally.

Different sources of data (literature, observation, and interviews with dwellers and professionals) are layered onto each other and triangulated to ensure the validity of the study.

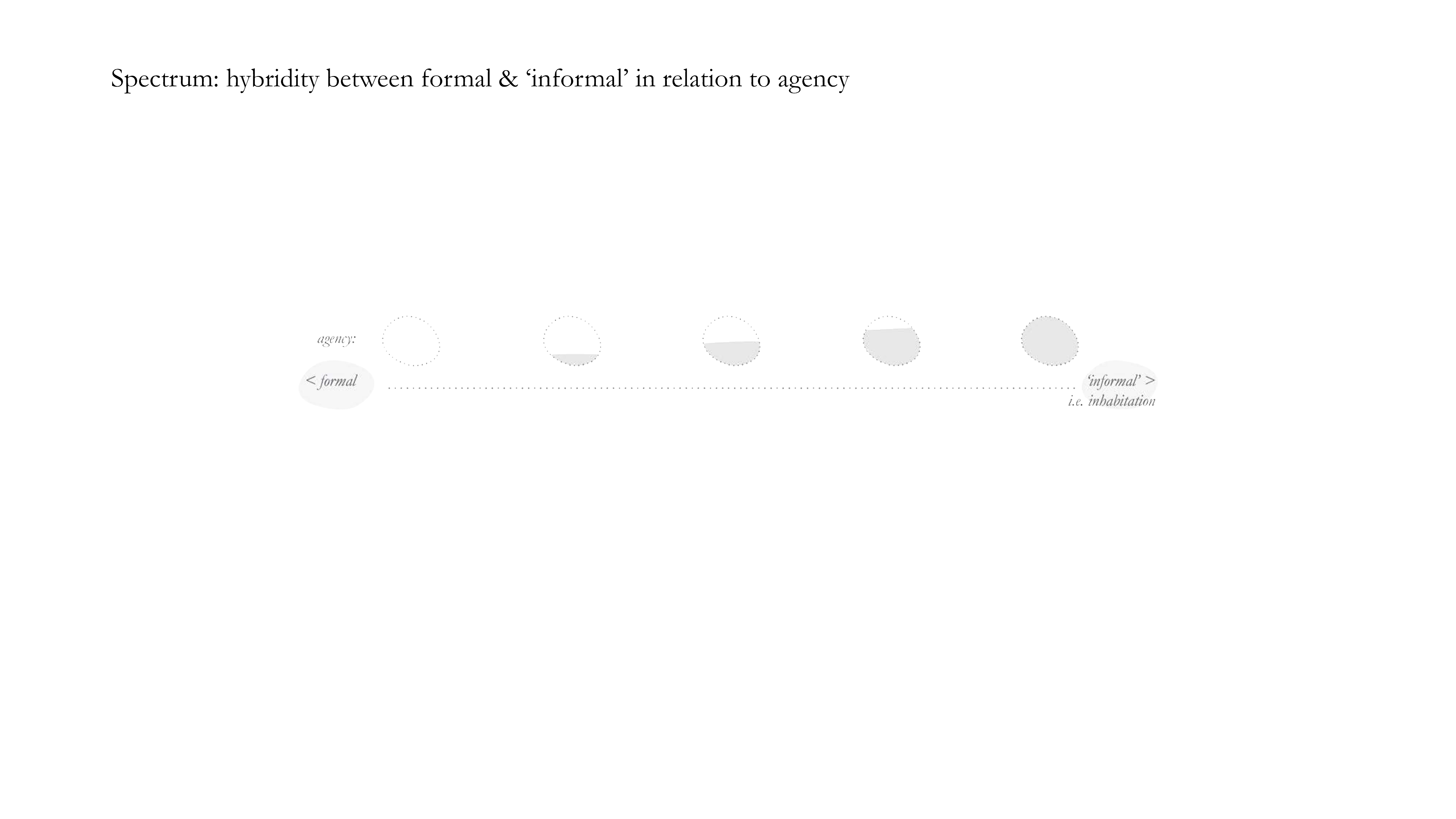

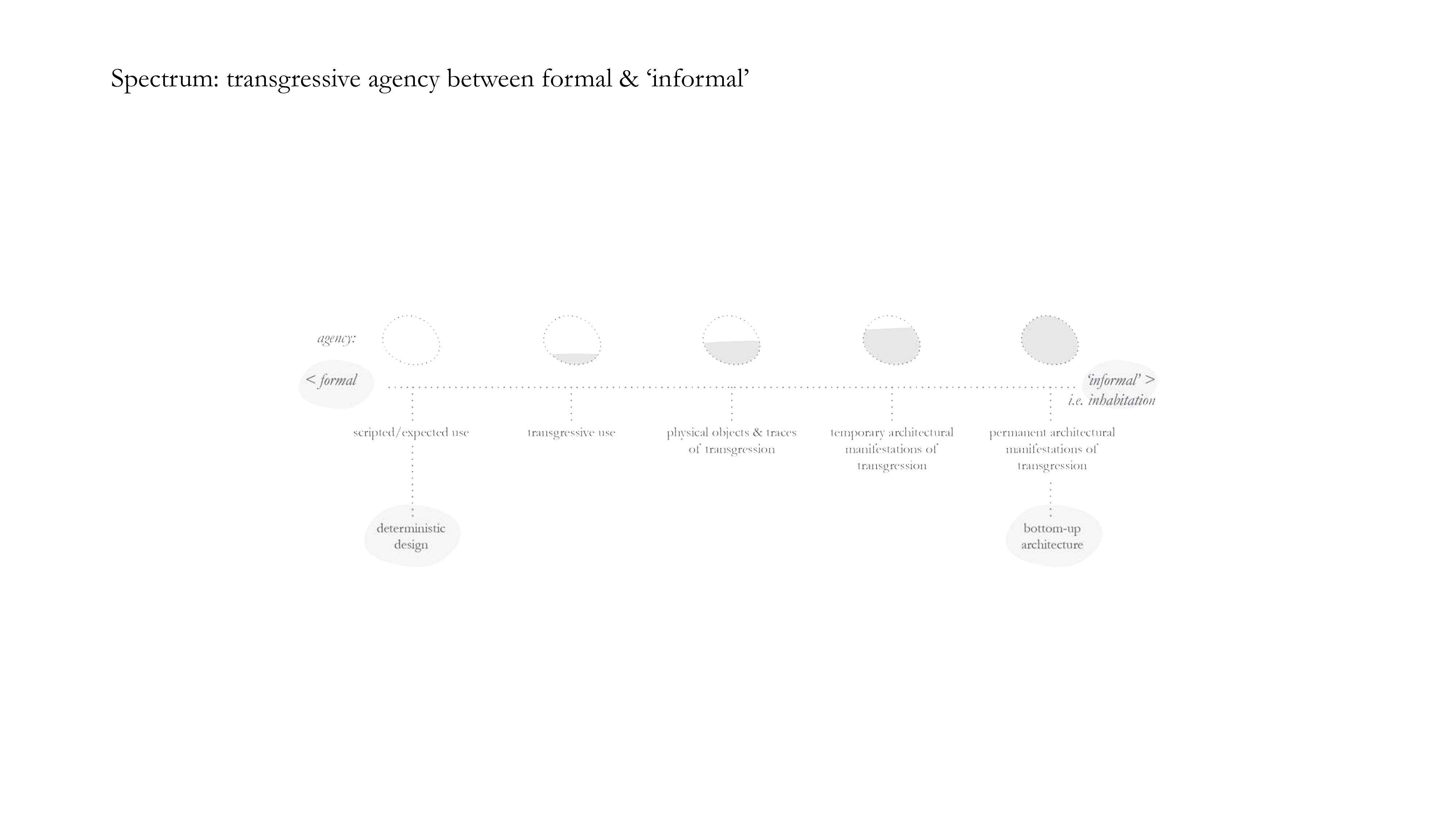

Rather than oversimplifying the formal and informal as a binary condition, it is essential that such concepts are understood along a spectrum, recognising hybridisation instead of difference.

Agency, defined as the creative action of individuals to induce change, also varies across the spectrum.

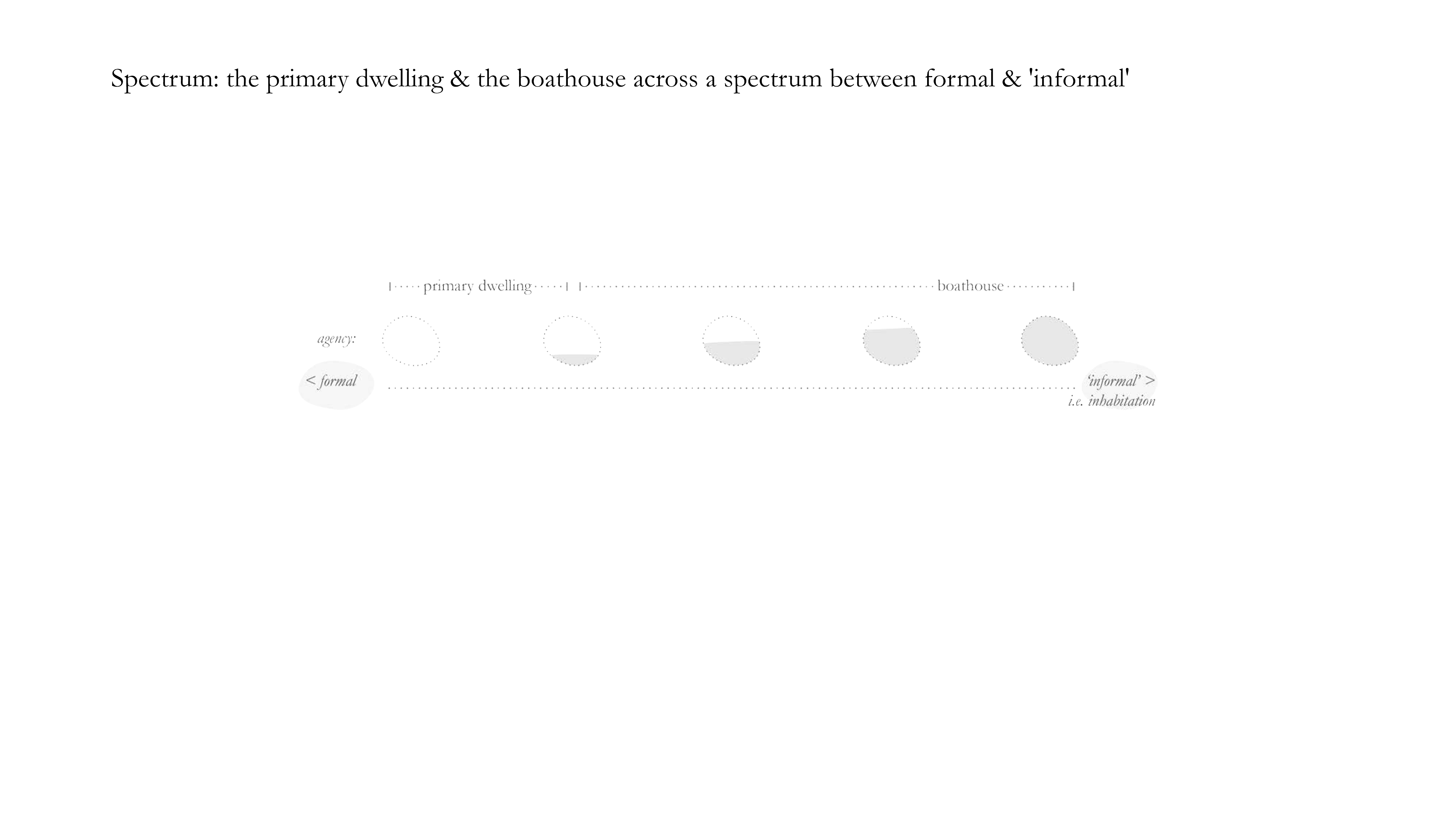

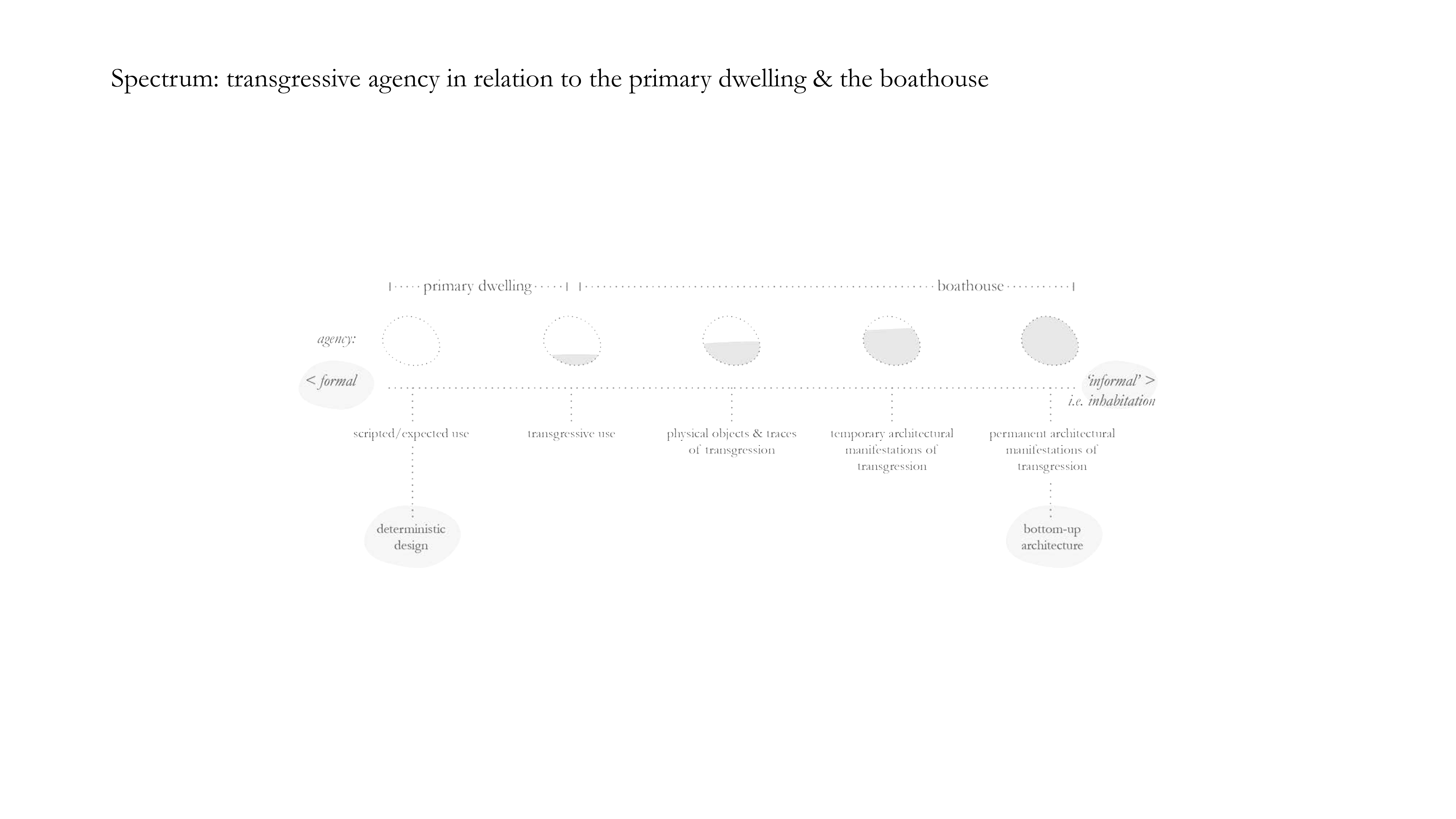

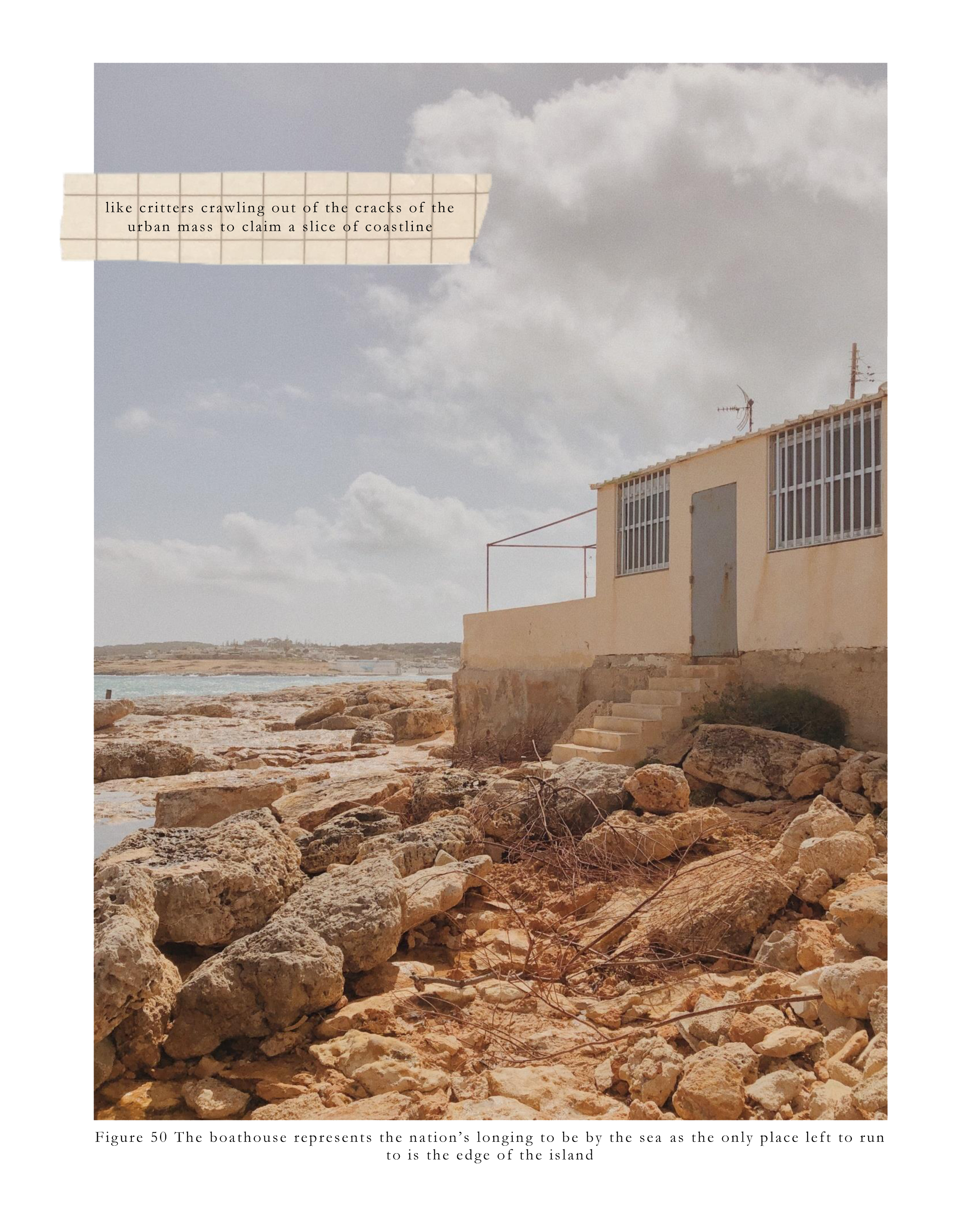

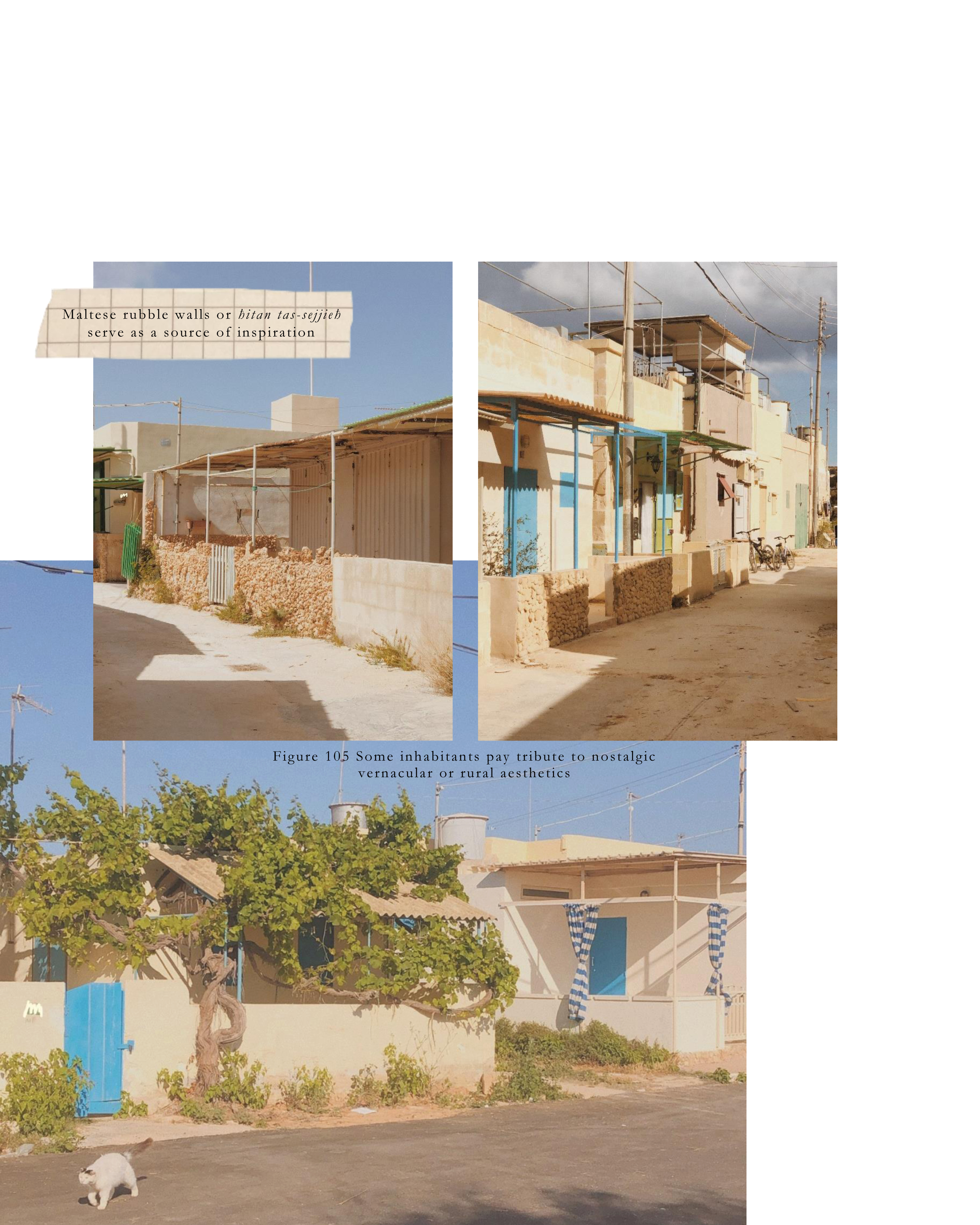

The study recognises that inhabitation and transgression of formal architecture occur across a spectrum. While this is not a dissertation about boathouses, the boathouse serves as a means of exploring agency & inhabitation within the local context. In most cases, the boathouse serves as a secondary seasonal dwelling, verging closer towards the ‘informal’ and inhabitation.

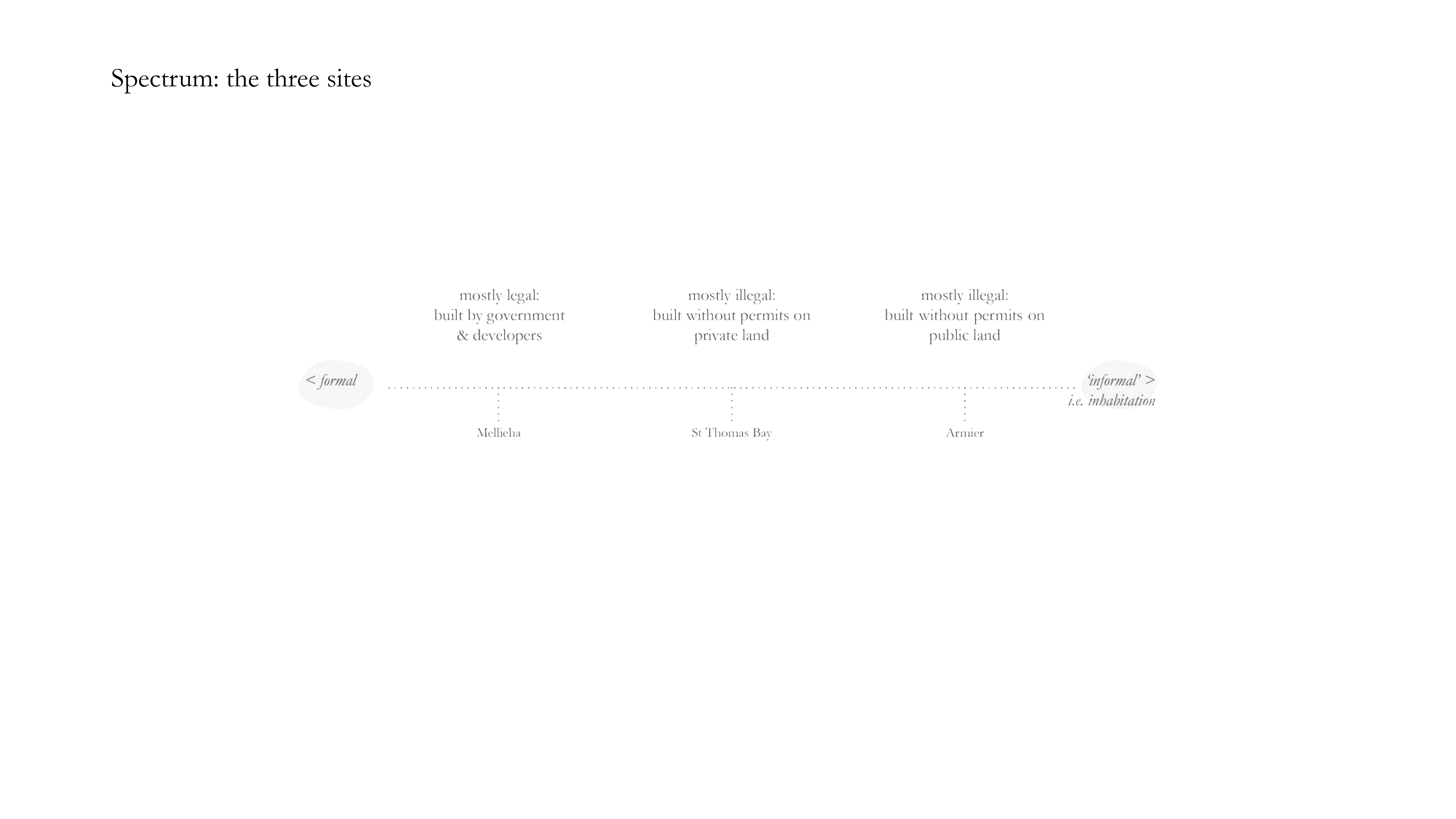

The three fieldwork locations, selected based on the largest number of boathouses and area, are Armier, St Thomas Bay, and Mellieħa (beneath Gerbulin Area and Santa Maria Estate). The three sites too exist along a spectrum in terms of their origins.

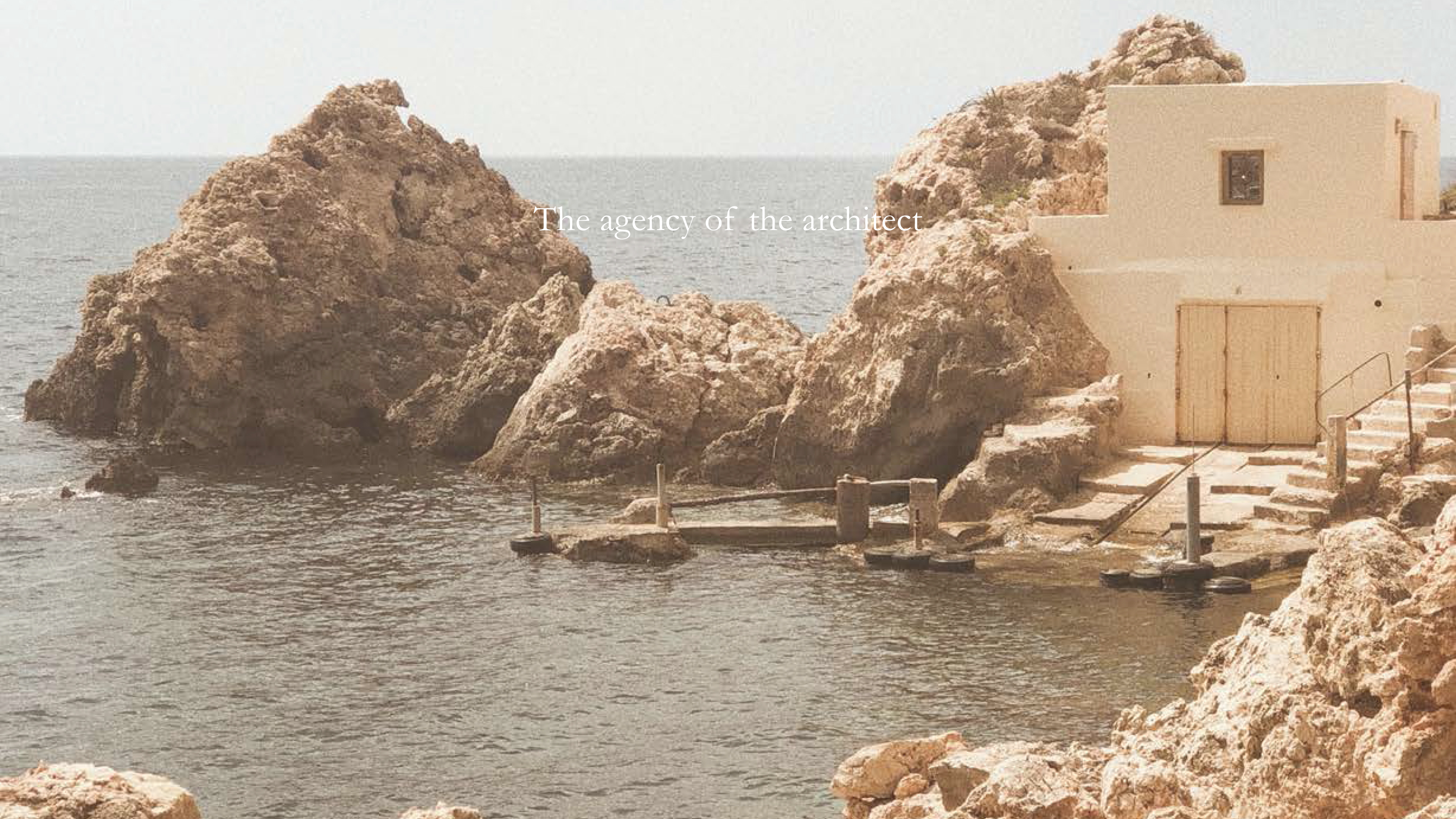

Such settlements are situated by coastal peripheries. On an island, we are even more susceptible to categorising land and sea as a duality; however, the transitional space between the two opens new opportunities of hybridity. Their marginal setting endorses freedom, endowing such in-between realms with a sense of otherness.

Thus, the coast emerges as a forgotten fantasy open to all possibilities while tempting playfulness and transgression. “A border is an undefined margin between two things. ... It is an edge. To be marginal is to be not fully defined” (Levy, 1993, p.73). The gaps which open up at such edges allow the inhabitants to claim them as their own and make a space for themselves.

At the boundary between land and sea, we play with the boundaries of architecture. Its peripheral qualities make the coastline a space where terms such as ‘architecture’ and ‘architect’ can be contested and negotiated, boundaries are transgressed, and formal distinctions are blurred.

The dwellers interviewed welcomed me into their homes and shared their life stories with me. They acted as co-researchers in this study. The social connections formed with the participants was one of the most meaningful outcomes of this research.

thematic discussion

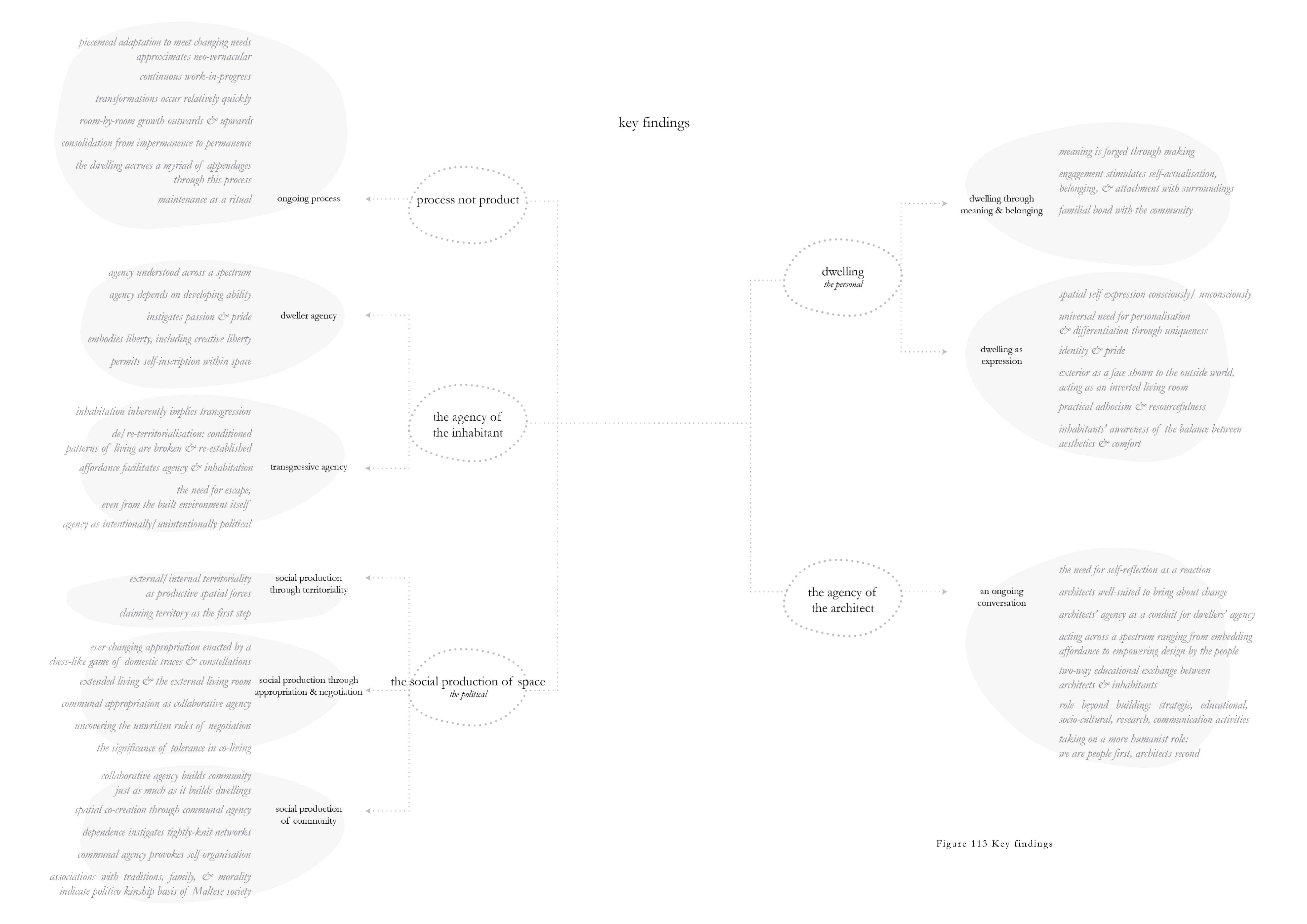

Theories of liminality suggest a continuum between creating and experiencing space. Such a reconceptualisation of architectural time hints at the idea that completion is an illusion, constituting only a single moment in a building’s lifetime and signifying its beginning rather than its end. Redefining architecture as ongoing and unfinished accepts it as a never-ending work-in-progress open to incremental change.

The unending evolution of dwellers’ needs and wants manifests as a succession of changes and adaptations of space through inhabitation.

Outward extension represents extended dwelling as a gesture of life pouring onto the street.

The transition from impermanence to permanence connotes improved resilience, comfort, and liveabilityas part of gradual change. The initial state of impermanence is usually strategically executed for the sake of quick appropriation and claiming territory until it is secured and made more durable and habitable.

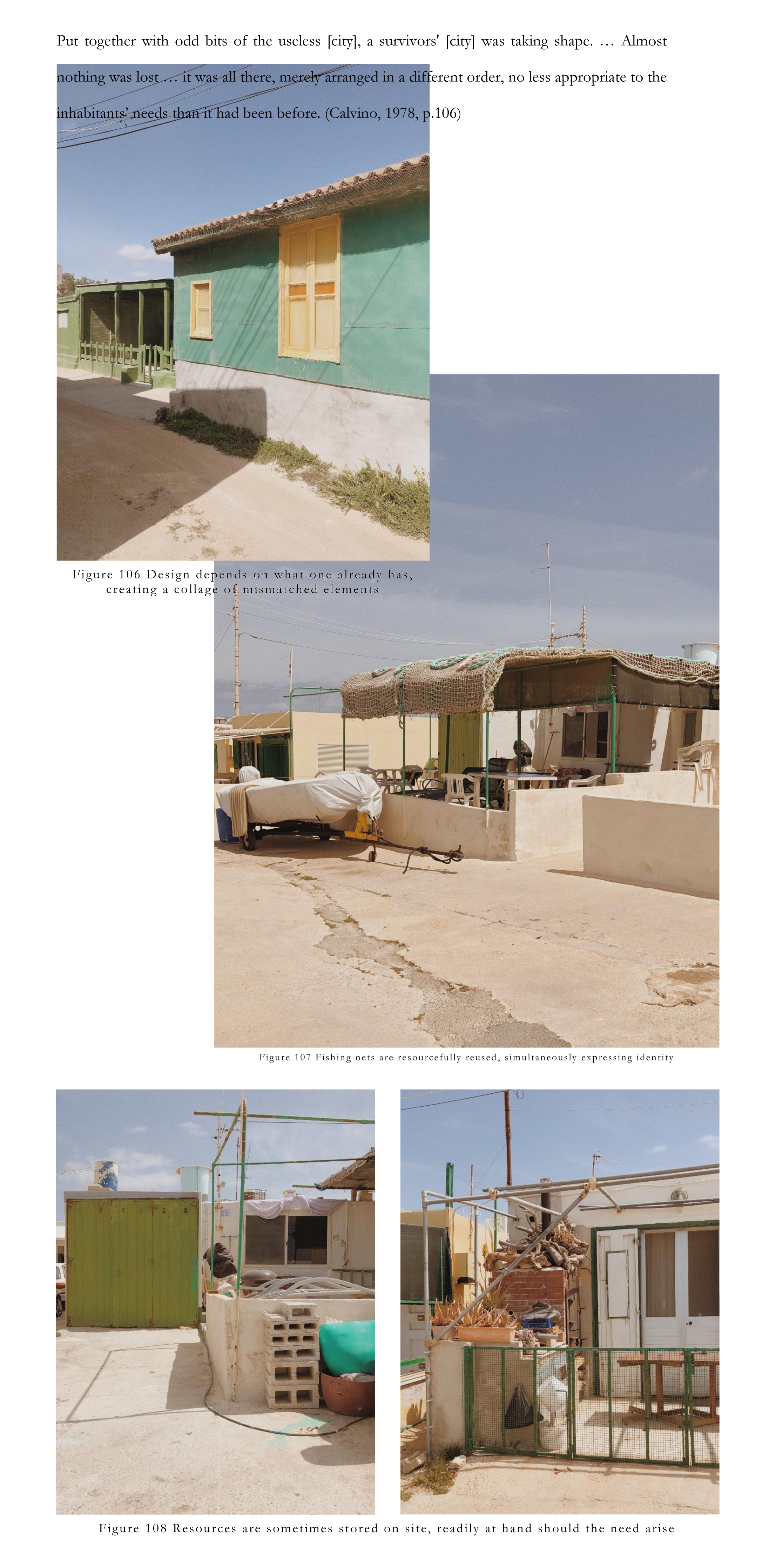

Extended living and accumulated permanence imply all kinds of ancillary functions and integrated facilities as the boathouse accrues a myriad of appendages. These appendages can be interpreted as inevitable traces of living, creating a secondary village of support

structure as a consequence of human deposits and accretions clinging onto the coast.

As part of an ongoing process, maintenance is treated as a seasonal ritual, symbolising the care & dedication invested in one’s space.

Visiting the sites across different times of year allowed seasonality to be explored in terms of what remains. Once most of the population relocates back to the primary dwelling in winter, the settlement empties, like a mollusc that migrates leaving its shell behind.

The residual appendages range from metal frames stripped of their enclosures, to folded chairs seemingly-forgotten in the parapett and patiently waiting for their inhabitants’ return.

The fallacy of passive users incapable of transforming space must be replaced by the notion of active and creative dwellers who are able to not only change an existing space and its meaning, but to create a new space themselves. This potential to contribute to one’s environment is the essence of agency.

As humans, we experience an innate urge to make stemming from the “latent architect” within each individual. This instinctive capability and creativity should not be inhibited, but developed further.

Thus, “the [dwellers]’ experiences construct the architecture as much as the architect”

(Bo Bardi, n.d., as cited in Sara, 2013, p.54).

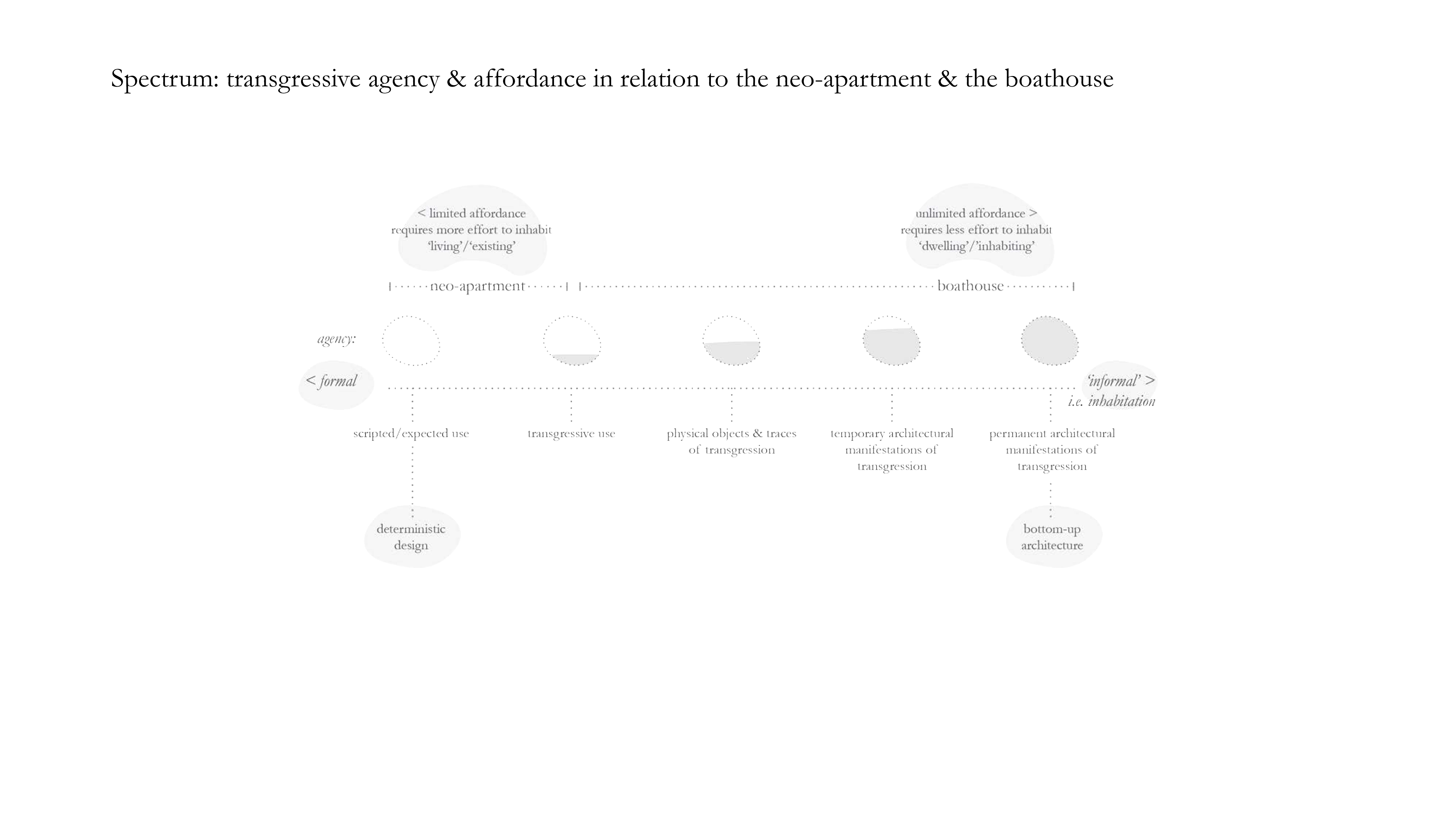

Dwellers’ agency and contribution are explored along a spectrum.

When questioned about their spatial contribution to the boathouse, most dwellers proclaim that as far as they are able to do so, they will create and adapt the space themselves. This in itself allows them to develop their skills and abilities, additionally imbuing the space with passion and pride. Moreover, the boathouse grants more liberty in fulfilling their wishes than the primary dwelling as the absence of regulations compels people to experiment and contribute to architecture. Personal contribution to the boathouse encourages dwellers to self-inscribe and weave their own narratives within space, infusing the process of caring for their boathouse with meaningful memories.

If inhabitation intrinsically entails creative agency and contribution to a greater or lesser extent, then to inhabit is to transgress. The conscious exclusion of inhabitation insinuates that formal architecture is choosing to ignore an elemental fact of life: an unavoidable and often subconscious manifestation of living and dwelling.

At one end of the spectrum, one may question how dwellers, as creative agents, inhabit and possibly transgress formally designed space, i.e., designed by an architect. At the other end of the spectrum, one could explore how people transgress the boundaries of formal architecture by creating architectural space themselves. This verges deeper into the realm of bottom-up architecture and extends the notion of inhabitation beyond the occupation phase to the stages of design and construction too.

Inhabitation, being an inherently transgressive act, can be framed through deterritorialisation as a process of breaking away from patterns of living conditioned by space, and reterritorialisation through which people find their own patterns.

The boathouse is well positioned to explore de/re-territorialisation as it is not always a predefined building which is then appropriated, but it is itself a process of appropriation.

Affordances define potential actions and meanings relative to space, hence affecting one’s agency. An environment offering restricted affordance demands more energy to resist and re-establish patterns. On the other hand, the boathouse is open to appropriation, affording infinite ways of engaging, manipulating, and inhabiting. The spectrum of affordance and agency between boathouses and apartments was conjointly studied in the researcher’s Thesis Project alongside this dissertation.

The remoteness of the boathouse lends itself to the sense of escape or żvog (release/escape) it exudes. The routine and everyday problems entangled with the primary dwelling are all but forgotten when fleeing to the boathouse. Thus, the need for escape can also be read as a form of transgression.

In contemporary discourse, agency carries political undertones of protest, which need not be interpreted as negative; it is a claim for power. While agency can be political, it sometimes emerges as unintended power. Transgressive agency can materialise as an accidental by-product of inhabitation. After all, the agency of forming one’s environment is a primal and natural habit.

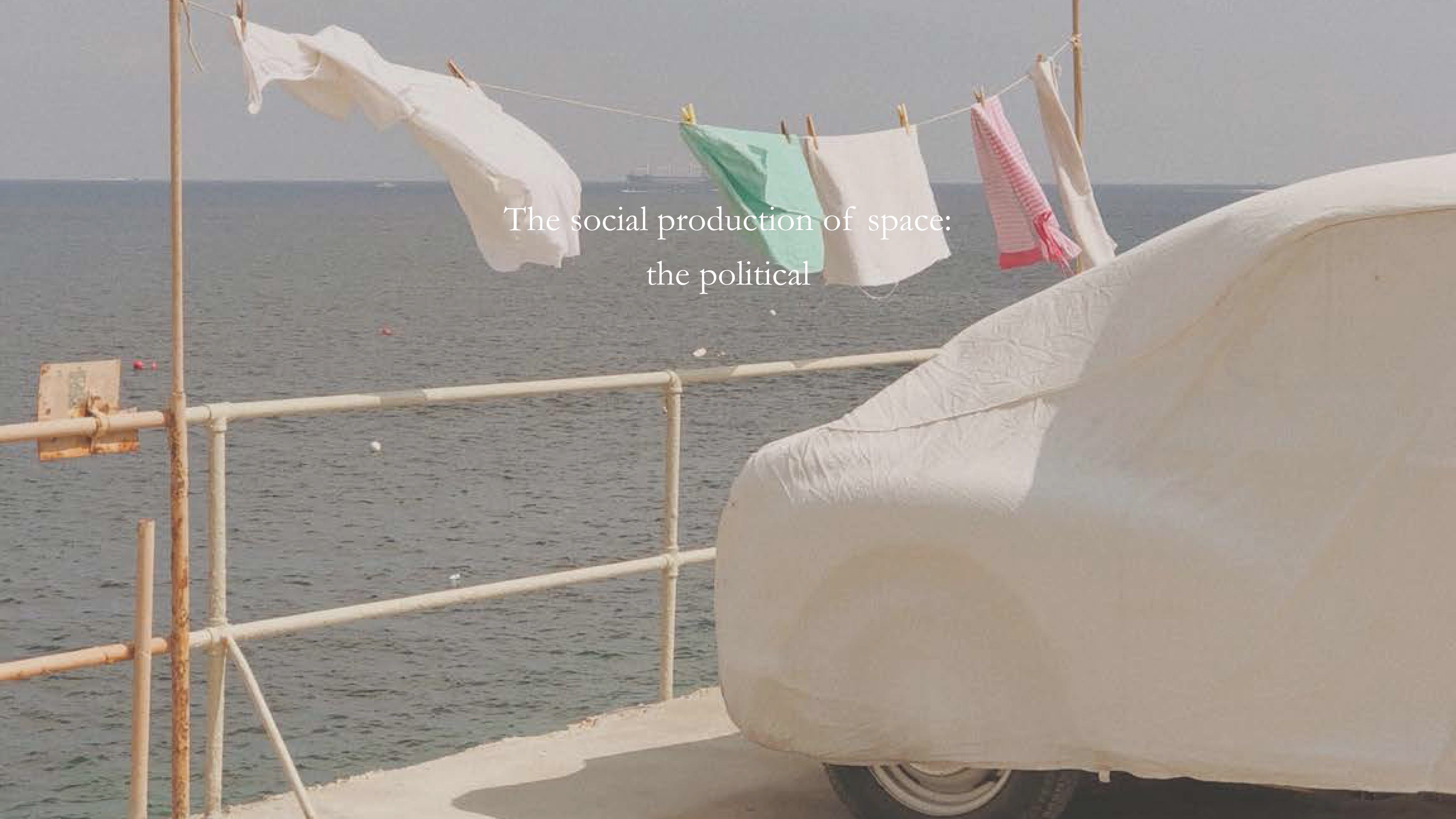

The reimagining of space from abstract container to space as active and socially produced was propagated by Lefebvre (1991). The liberation of our agency contributes to the creation and transformation of space, be it in terms of material or meaning. Thus, space as a social construct is dependent upon human action and agency.

The social relationships embedded within space make it politically charged and can be envisioned as “lines of power and agency written and unwritten in space” (Boano, 2013, para.16).

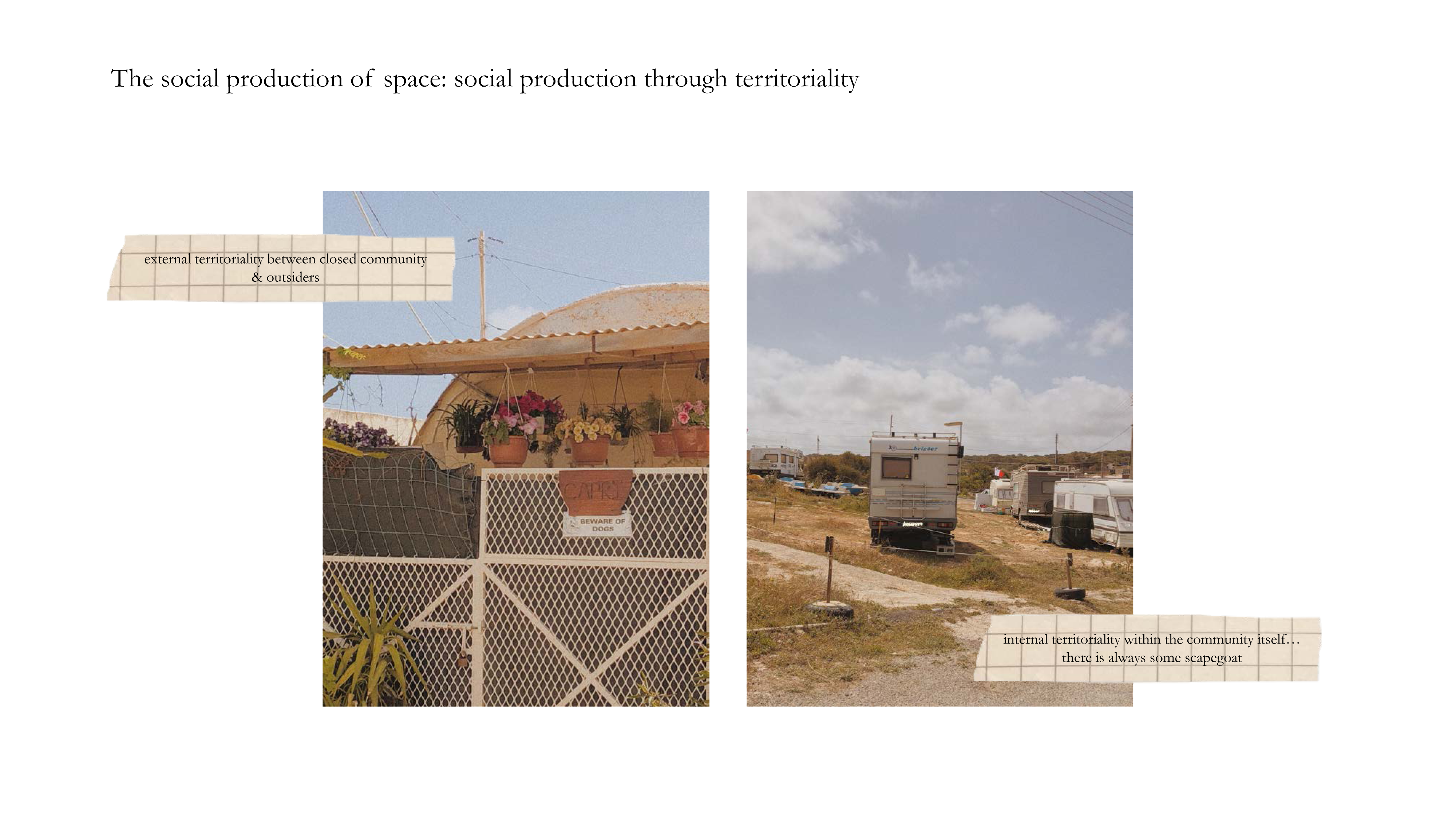

The political dynamics of space are also rooted in territoriality, a socio-spatial relationship by which people seek control over other persons and resources through the control of space.

The initial move in consolidating one’s territory involves setting boundaries to define one’s property and lay claim upon it. This first step of infiltration is facilitated by pre-fabricated components. Although such land-grabs are more controlled today, they are still visible towards the peripheral hinterland of such settlements at the borders with unoccupied territory, making for active zones of no man’s land in which boundaries are constantly negotiated. Once base-camp has been secured, the next phase involves further expansion and colonisation.

Under these conditions, space is produced in a scattered and fragmented way arising from spatial appropriation, which subverts space through unanticipated modes of inhabitation.

Appropriation is a political and transgressive act with the potential to create new space and meanings by the fluid redefinition of social space and innovative interchanges between the public and the private.

These gestures are often manifested through small traceable acts of production or transgression which can be read in space. “To live means to leave traces” (Bejamin, 1986, p.155), and it is these remnants and by- products of everyday life and dwelling that intertwine to create the rich narratives which enliven the architecture of inhabitation.

Ever-changing appropriation is enacted by a chess-like game with its own set of rules where domestic traces replace the usual pawns and bishops.

The material and meaning of social space is continuously made and remade, enacting its contested nature. Social negotiations and intersecting agencies partake in the endlessly active reconfiguration of space.

Apart from the ever-changing constellations of intentionally/unintentionally-politicised paraphernalia varying from potted plants, dining sets, and barbecues, to laundry, vehicles, and chalked hopscotch, space is also appropriated by parapetti and canopy structures, some of which evolve into external living rooms with the finishes and fixtures to match.

Apart from uncovering the unwritten rule sof negotiation, such manifestations also represent a sense of tolernce which is missing in most urban settings today.

Boathouse communities make basic human nature perceptible by hosting slightly more extreme conditions to reveal otherwise-unclear human patterns and behavioural code. The concentration of life in such settlements distils how all of us inhabit and dwell.

Despite their apparent chaos and lack of top-down control, bottom-up settlements exemplify an emergent order and capacity to self-organise emanating from a “multiplicity of small acts” (Ceridwen et al., 2013, p.214). It is by virtue of this meshwork of productive forces that the community can collaborate in the collective construction of its spatial identity.

Collaborative agency can build community just as much as it builds dwellings.

These tightly-knit networks are revealed in the community-based system of supply and knowledge; it would seem that dwellers are a lot more dependent on each other in boathouse communities.

Communal agency provokes self-organisation, perhaps most apparent in activities organised by the community itself, many a time quite spontaneously. Perhaps the sense of community is strengthened by the common threat of eviction and mutual transgression.

Such settelemts tend to feed into the myth of an ideal community. furthermore, links with traditions, family, & religion act as tropes in attempting to legitimise their existence & indicate the politico-kinship basis of Maltese society.

The origin of architecture and dwelling is often attributed to caves, nests, shells, and other forms of shelter which inspired the first signs of building by man, heralding stories of the primordial hut. However, the genesis of dwelling is frequently reduced to the need for physical shelter, overlooking the sheltering of the soul linked to the psychological requirements of dwelling.

Like a nest for our embodied selves, the house materialises from the act of moulding the earth around our bodies. Hence, the house is not merely the built house, but it is created and adapted through inhabitation and experience: “One must live to build one’s

house, and not build one’s house to live in” (Bachelard, 2014, p.126).

Heidegger (1971) further defines the relationship between building and dwelling: “To build is in itself already to dwell” (as cited in Sharr, 2007, p.39).

The process of dwelling and actively transforming one’s context into a supportive habitat inherently bestows meaning upon those surroundings. When the people who make are the same as those who dwell in a place, it inescapably ignites feelings of embeddedness within that space and community.

Apart from adapting the environment to suit one’s needs, self-actualisation and self-expression emerge as important facets of this process. Home is both an extension and an expression of the self, whether consciously or unconsciously.

Uniquely personalised spaces and façades become the realm for differentiation through the expression of identity and pride. The outdoor space serves as the face shown to the outside world with the parapett acting as an inverted living room by putting the family on display.

Many boathouses express signs of resourcefulness, conveying practical adhocism, a process by which immediately-available resources are assembled in juxtaposition to fulfil a specific need. Leftovers from the primary dwelling are often recycled at the secondary boathouse in the form of architectural bricolage.

By acknowledging the dweller as a creative agent, this study questions

formal architecture and the agency of the architect. This is interpreted not as a threat, but as an opportunity to self-reflect as a profession while opening up architecture to include and enable the inhabitant and the everyday processes of inhabitation, generating new forms of hybridity and co-creation.

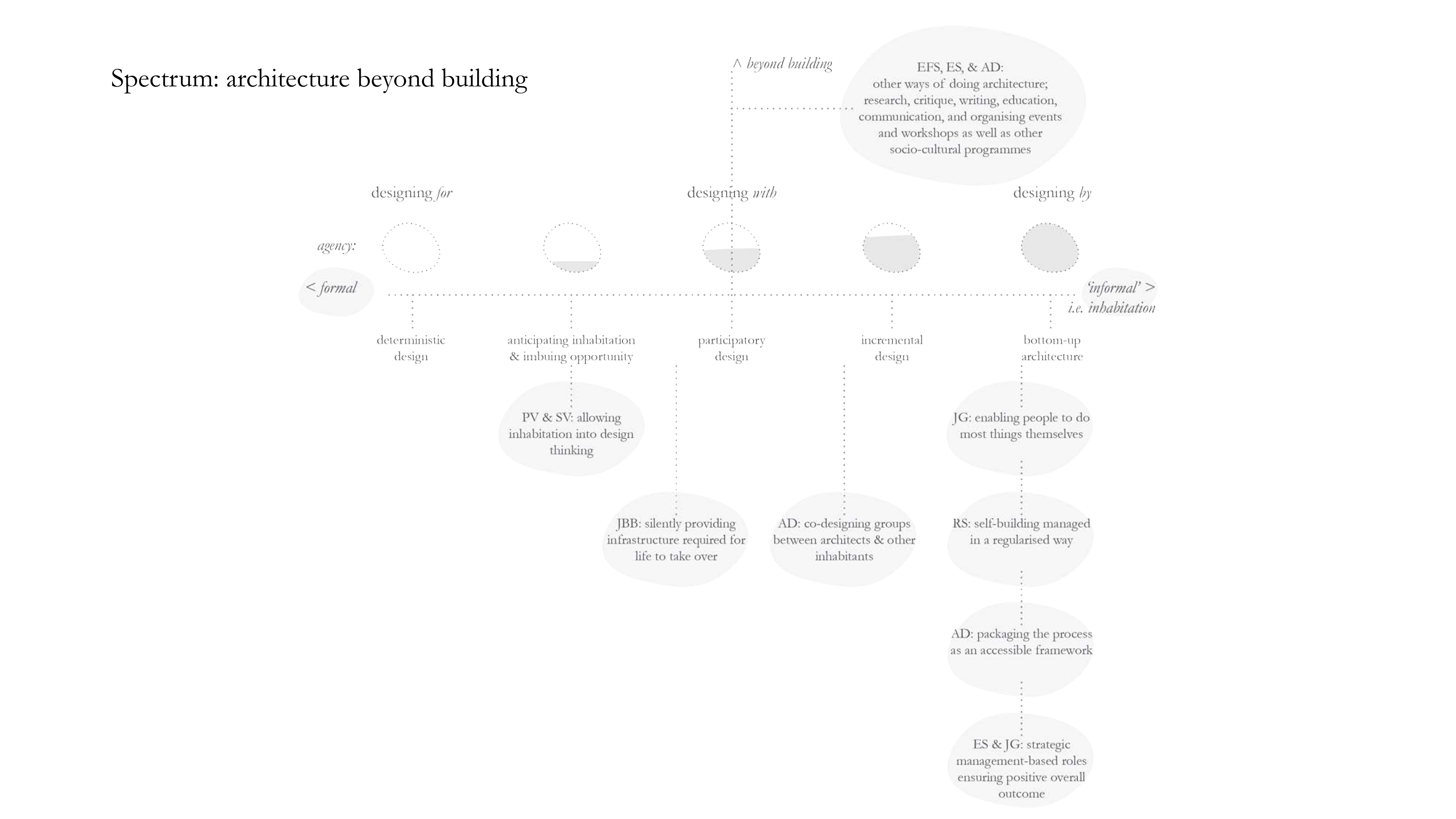

To further explore how architects can enable the architecture of inhabitation, we must understand that our involvement can range across a spectrum, from formal to more ‘informal’ approaches and contributions.

The proposed shift in mindset reimagines our own agency as architects as a conduit for dwellers’ agency and has the potential to transform our role by expanding our scope beyond building,

simultaneously reprioritising humanistic motivations.

The proposed shift in mindset reimagines our own agency as architects as a conduit for dwellers’ agency and has the potential to transform our role by expanding our scope beyond building,

simultaneously reprioritising humanistic motivations.

Thus, the notion of architecture beyond building introduces a new axis to the spectrum.

While realising that this is an ongoing conversation with no definite conclusion, initiating the dialogue is already a step in the right direction in exploring alternative ways of doing architecture.

The passion and motivation behind this dissertation have always lied in the potential recognised in individual human beings. This creative potential and agency should be harnessed as well as celebrated, not only as a productive resource towards architecture, but also as a human right by nourishing self-actualisation and fulfilment.

These sentiments have made me question what kind of architect I want to become and my own agency. On a personal level, this study has fuelled my desire to pursue socially-relevant work and has inspired me to make an effort to involve and empower the inhabitant as much as possible through my own agency while intentionally seeking to create the right environment for collaborative relationships to blossom.

May this serve as a reminder of why most of us were inspired to pursue a career in architecture to begin with, i.e., to help people. This seemingly-simple purpose has perhaps become overshadowed by a multitude of other factors, yet it is vital that people remain at the heart of architectural intentions. People’s direct involvement in the field could only serve to ensure this, thus reorienting our primary ambition towards helping people help themselves in the bettering of their lives.