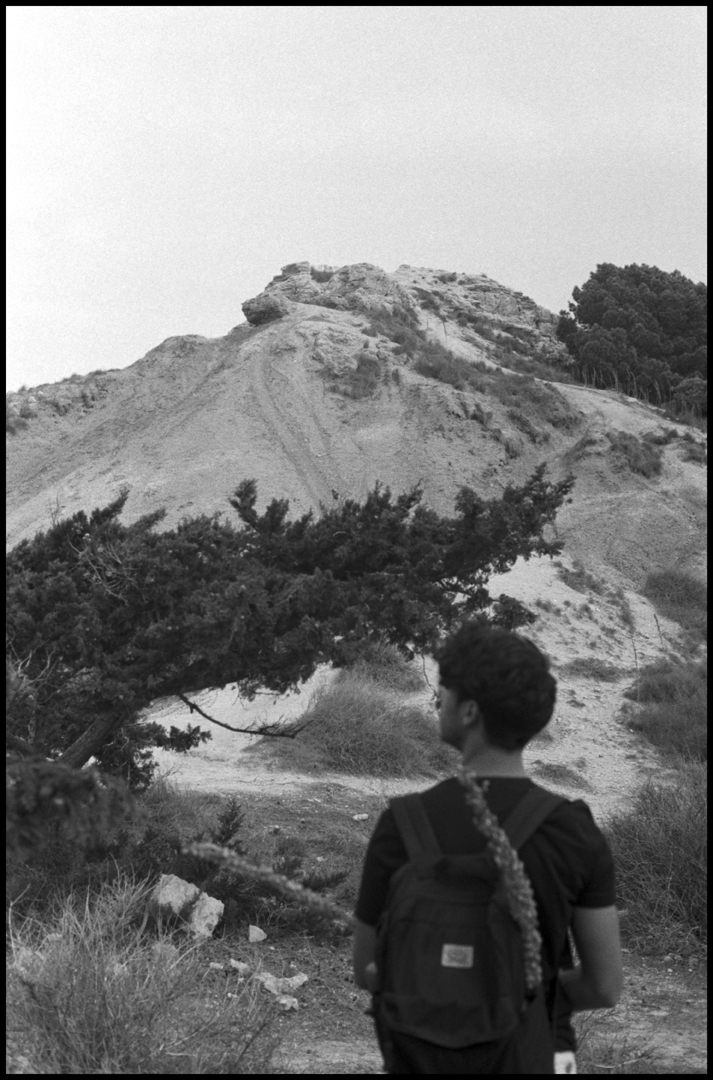

1. il-ġebla

english translation: the rock

2024

i speak the language of the earth

i feel my body slipping into synch with the rhythms of the earth, subconsciously waning & waxing on time. the rocks sing me to sleep sometimes. the grass is my bed, the moss my blanket & my head rests on pillows of cloud.

this is where i feel most myself (other than by the sea)… walking barefoot in the grass, marvelling at birds’ nests, foraging for four-leaf clovers & lying in the sun while indulging in fresh gozitan bread

gozo emerges shimmering in my mind

like a dream from childhood

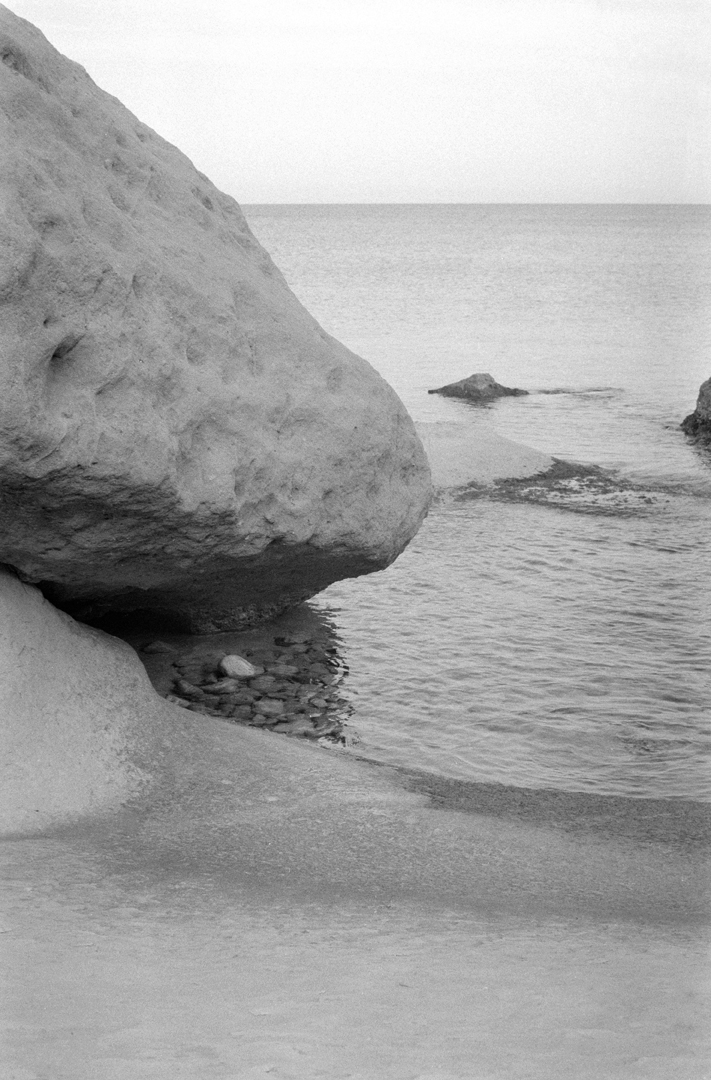

mushroom rock & other fairytales

ploughing patterns into the land

king of the beach

contemplations on bees & the secret worlds they create

scenes from some kind of outlandish dream

while the sea is still sleeping

we are built of the same rock,

the same sea,

the same sky

moulding to each other, meeting in the middle

2023

are you sleeping while i’m away?

your face seems softer each time i return; it’s as though time stops on the island when i’m not here... but perhaps that’s just one of the things we tell ourselves to hide in the dark.

2022

the golden days

& the living is easy

hands hard at work,

hands flowing like the waves

meditating megaliths

castles in the sky

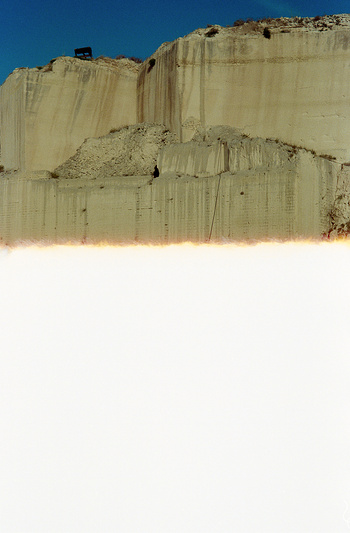

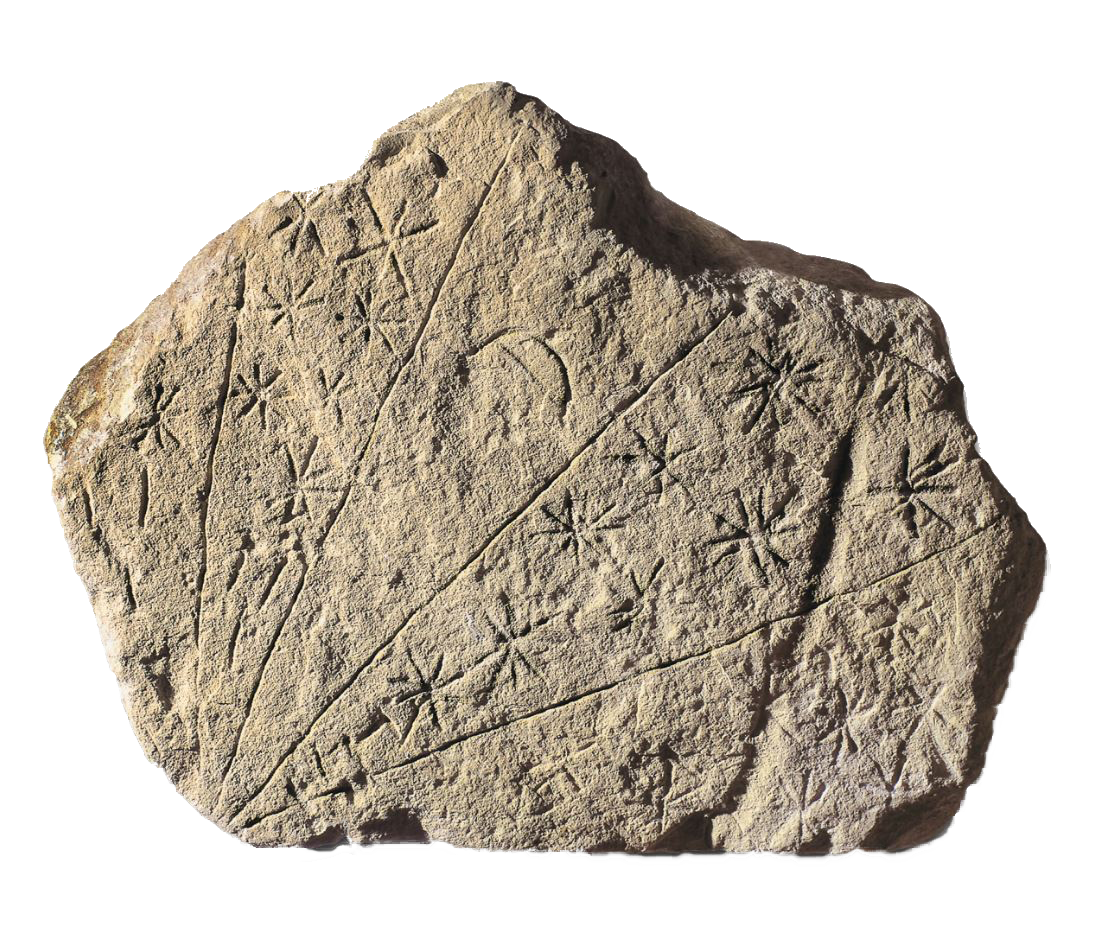

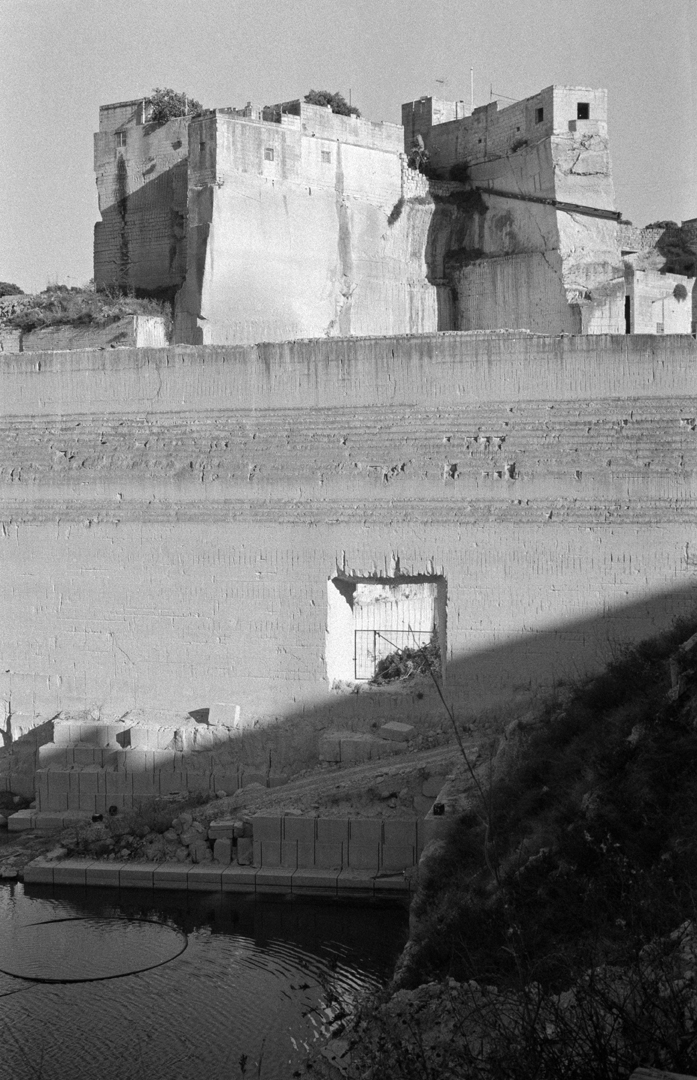

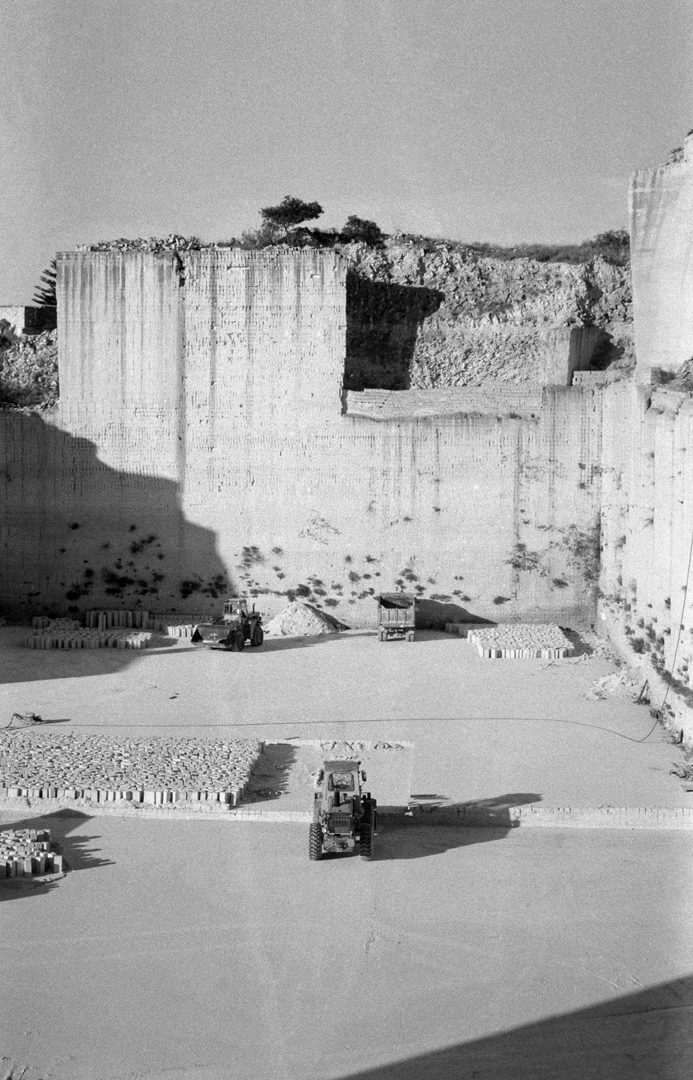

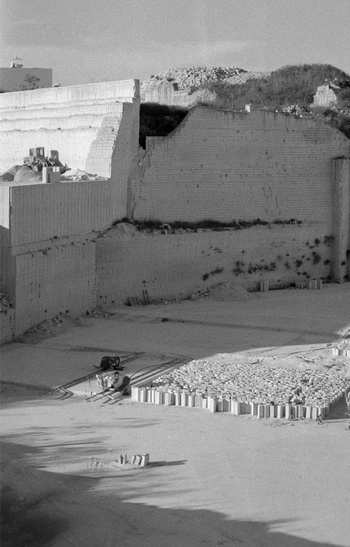

incisions & remains

a man-made crevice

slicing through time

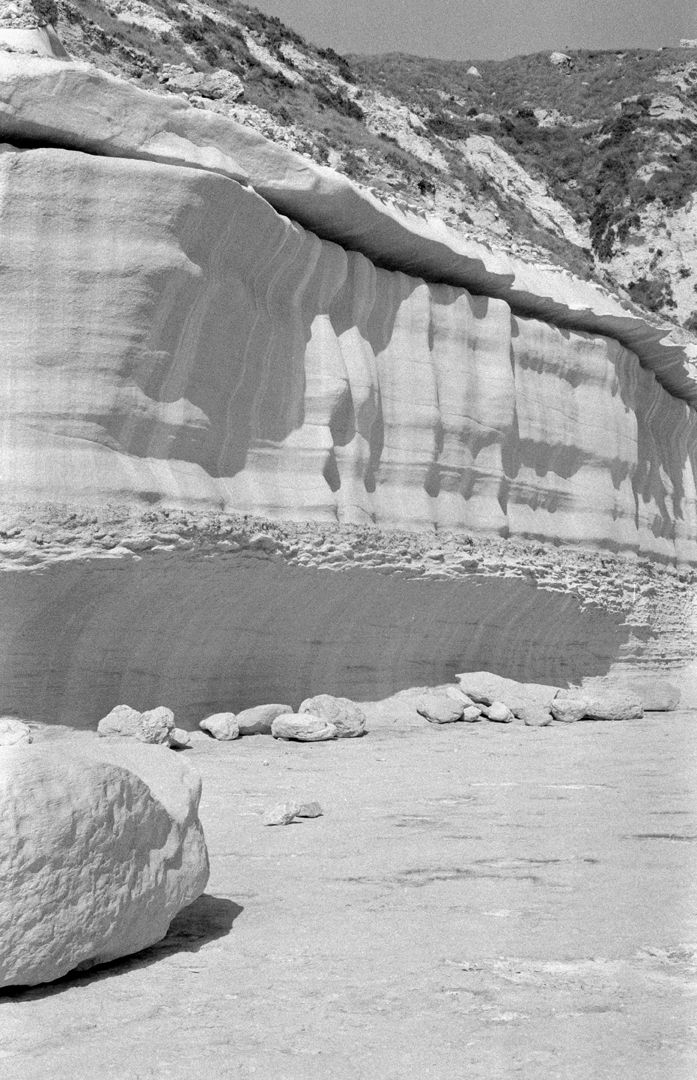

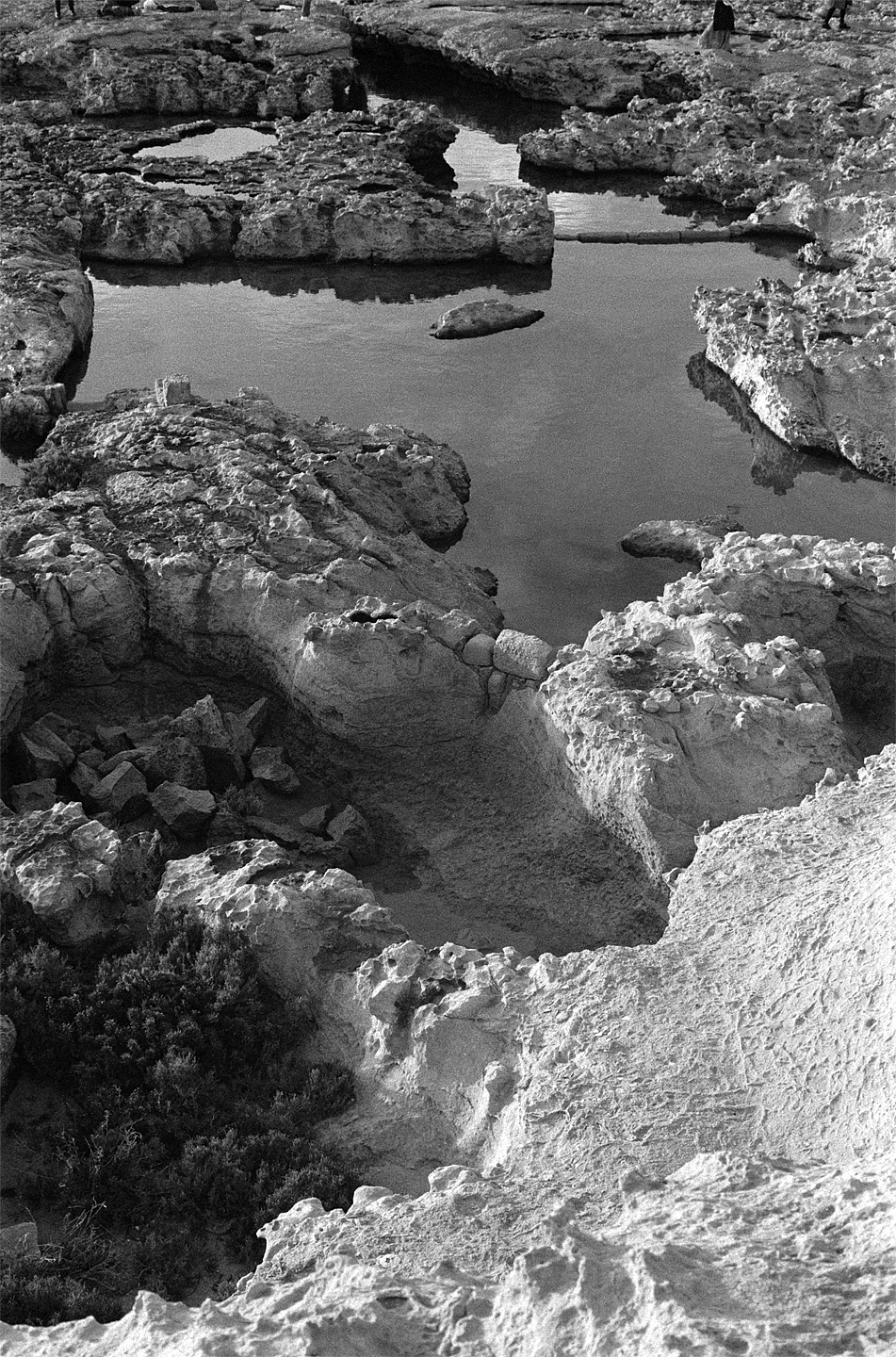

geological time is written in the rocks

a geological playscape

dust settles upon a lunar landscape

glittering seas

2021

looking for patterns in a scattered landscape

weaving new narratives from the disparate fragments left behind... it was the age of uncertainty, things changed slowly then all at once. we could all sense a new era on the horizon; so we distracted ourselves with the task of picking up the pieces, jumbling them up, & trying to form new patterns.

like floating white clouds on the horizon

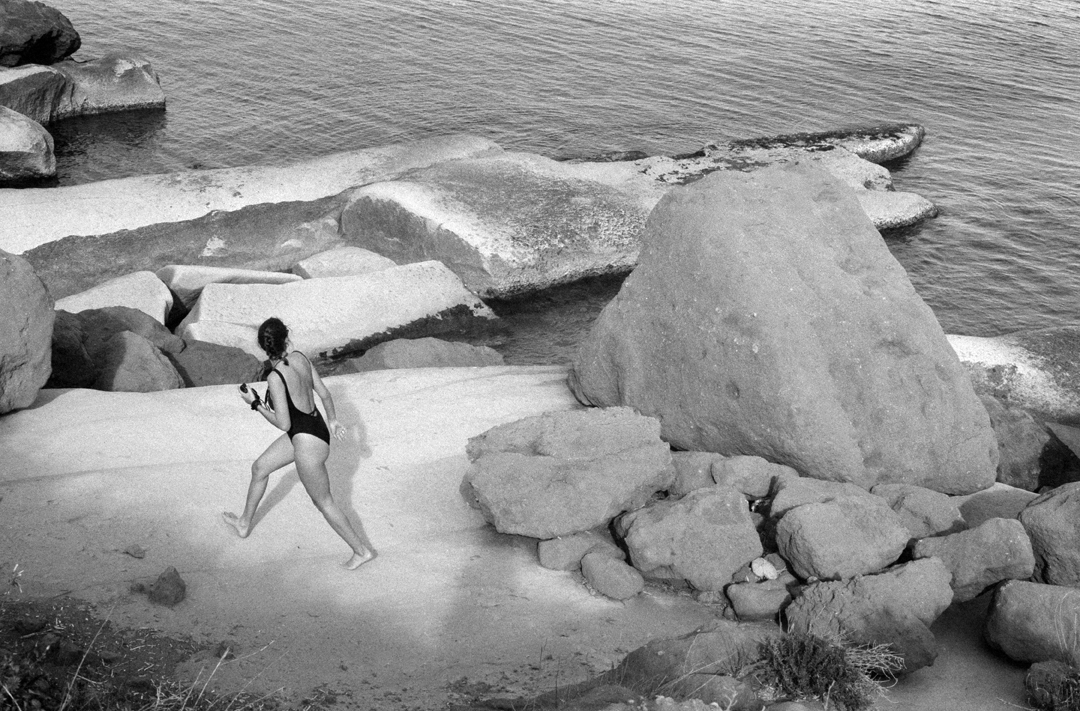

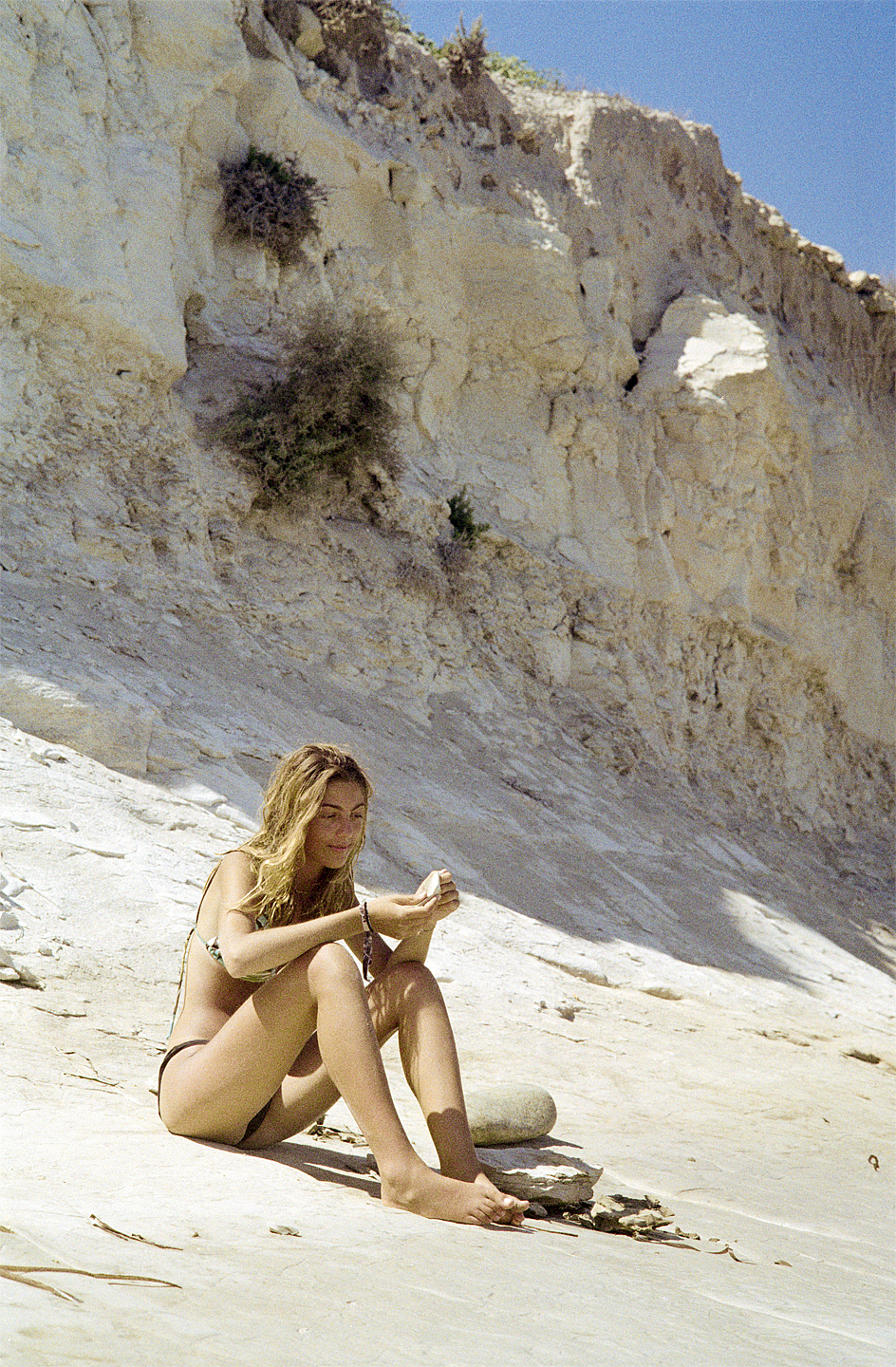

sirens who grew legs & climbed ashore

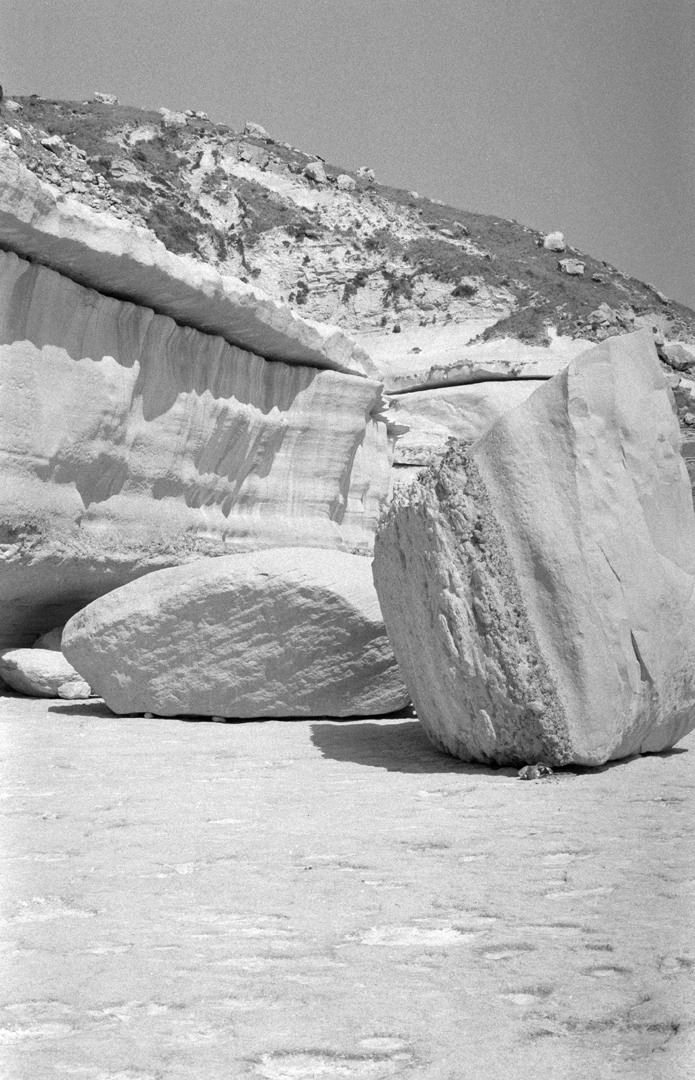

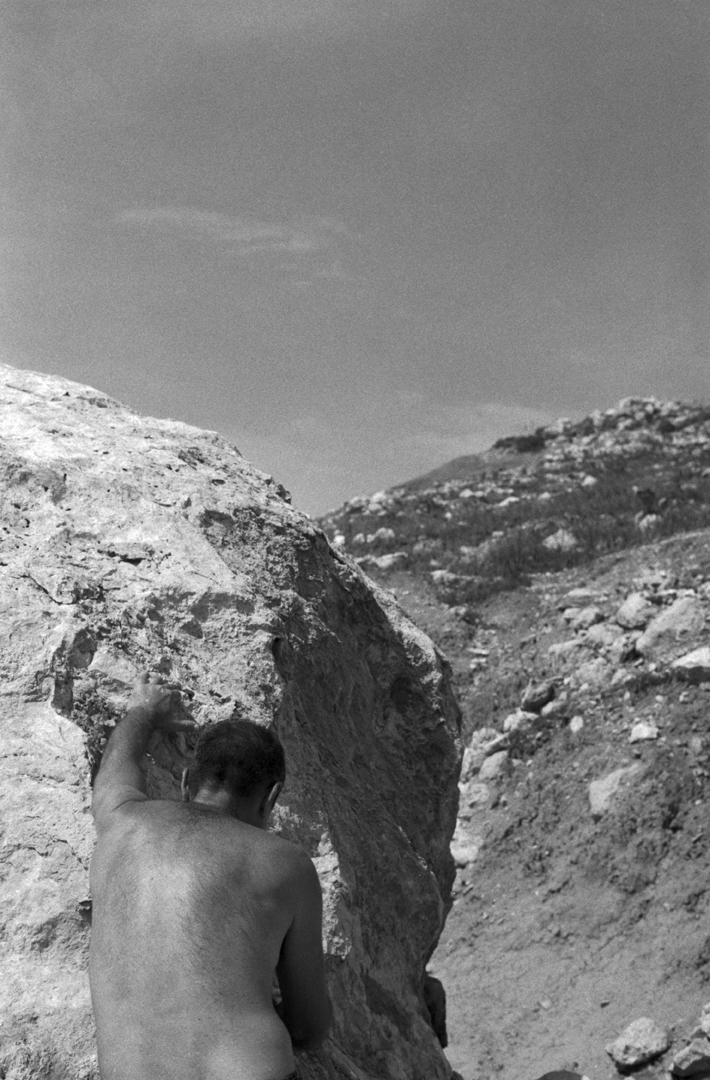

we are made of the same limestone we lie on & the sea we swim in,

their particles forever infused within our bodies

the island which shapes us,

such that we follow the same curves

the jagged edges of the island

are continuously slipping from under our feet

wrapped in dappled sunlight as we lay beneath the olive tree branches

boulders eroded slowly by the incessant soft kisses of the sea

ta’ rita

landscapes of infrastructure

2020

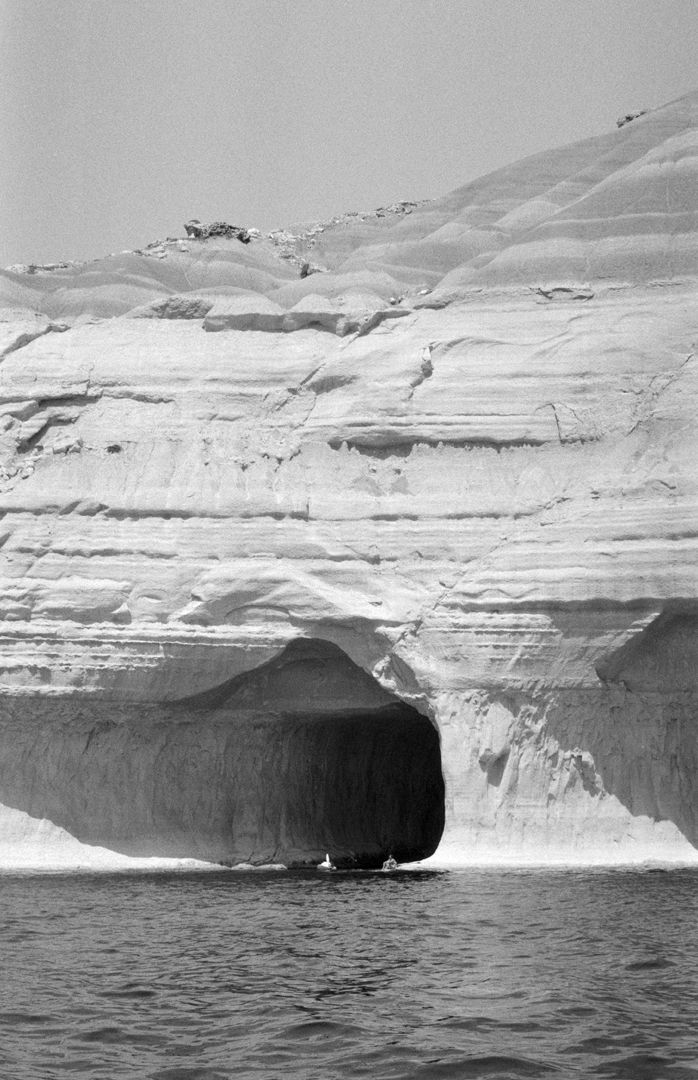

living in rocks by the sea

that summer the pandemic hit, we were like creatures crawling out of our homes to claim our own slice of seaside & sunshine

carved by water nymphs

as summer draws to a close, the coastal realm slowly becomes an uninhabited shell as we retreat to the island’s centre, leaving a string of traces behind

appendages of the coastline / human deposits

the architecture of inhabitation

the new doric

is-simenta:

what if islands just floated on the sea like rafts?

kappella fuq kemmuna

lunar landscapes

coastal extractions

fairy pools to bathe in

grottli telgħin mal-blat

dwellings, like seashells, cling onto the rocks & allows us to curl up in them

earth moulded by sea & sky

olive-picking & spiru

flower bed

2019

more stories from a limestone isle

reading the tales embodied within the rocks

ode to the sister island

ta’ krispu honey thief

the inhabited pathway

2018

upon returning to the rock

i experienced a newfound sense of what it means to come home. suddenly, the landscape i previously believed to be dull & uninspiring was emerging as an exciting & novel form, begging to be discovered. the rocks looked different now. their colour no longer appeared homogenous but lured me in, tempting me to wrap myself in their honey-coloured hues.

like ancient gods of the winds

pater & rock:

the smooth back of one against the rough face of the other.

2017

disposable daydreams

sweet memories of strawberry fields in early summer

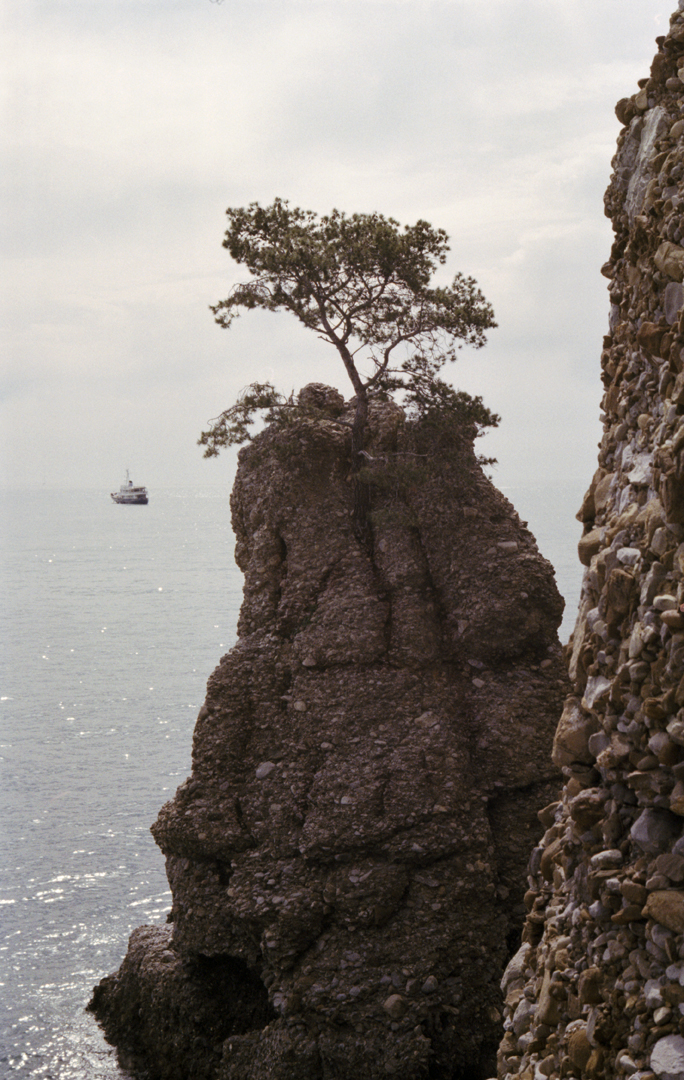

2. somewhere in the mediterranean

it’s not just a place, it’s a feeling

2024

let’s play mermaids

endless blue in sardegna

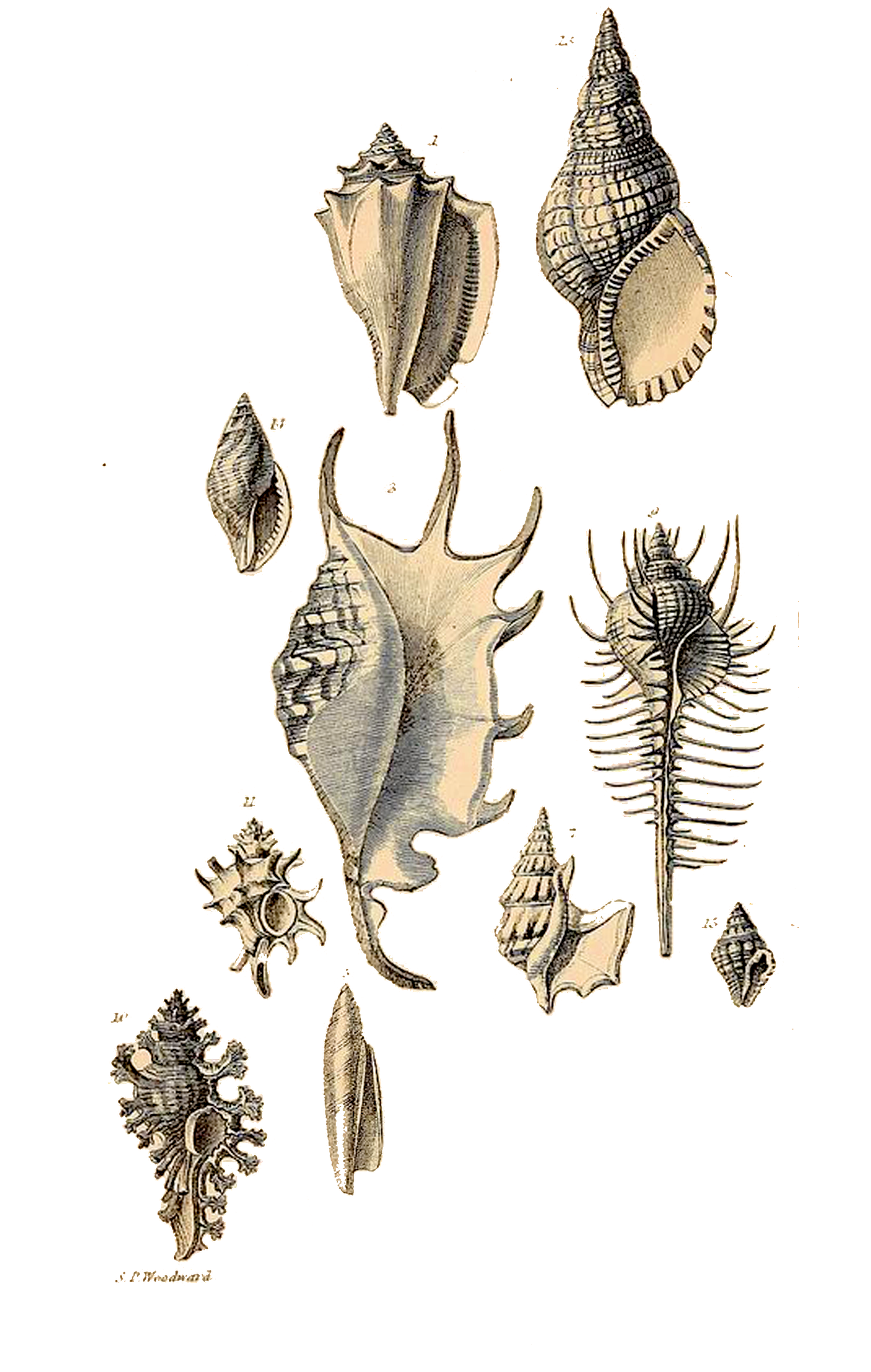

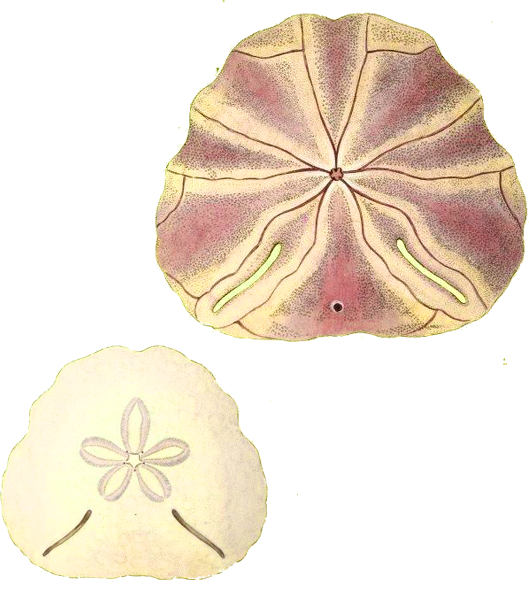

rock-cataloguing

in the shade of the juniper trees

spending my time exploring any new place imagining the lives lived behind its doors & windows, dreaming up narratives unfolding behind its facades & weaving connections through its streets

2024

granita per tre

slow days dozing under the lemon trees

2024

roman holiday

the beauty of being alone

portals to another time

stumbled into a massive board game that the gods play from above

overheard conversations in rome

2023

i went to talk to the sea today

summer’s end in siciliy

2022

sicilian roadtrips

il dolce far niente & other lessons on how to savour life

all streets in santa flavia lead to the sea… a dream-like town which materialises when least expected & refuses to be found when you seek it

lido livin’

lonesome petrol pump

some photos you don’t manage to take

live in your head forever

until you do

destinazione: caletta sant'elia

destinazione: isole egadi, favignana & levanzo

visions of the coastline:

stairs leading from the sea to an ancient fortress under which limpet-collecting nonni crawl

visions of the coastline:

when we cut into the land, are we making the sky bigger?

visions of the coastline:

cuts and protrusions in the rock seducing the sea to kiss it

children playing in forgotten quarries emulating ancient temple ruins

destinazione: cefalù

breakfast beneath the fig tree

la rocca

destinazione: scopello

goddess of the sea

destinazione: alimena

a little town right at the centre of sicily with a hill, at the top of which the rest of the island is laid out beneath you like a map

destinazione: noto

a convent airing its dirty laundry

destinazione: ortigia, siracusa

destinazione: ibla & ragusa

garden of the gods, suspended amidst the clouds

destinazione: scoglitti

destinazione: scicli

a town tucked away in a crevice overlooked by a monastery

cicadas chirping, the scent of fig leaf wafting on the hot summer breeze, winding roads between the olive trees as we traverse southern sicily

destinazione: agrigento

buried within the city walls,

a city of the dead exists encircling that of the living

an archeological daydream

destinazione: scala dei turchi

a cloud-like cliff emerges from the glistening water

destinazione: modica

2021

a day by the lake

a foggy arrival, a lakeside lunch, a hidden pasageway to the sea, watching children play as they climb onto a rock, a boat left to enjoy the lapping of the waves onto the shore, two hundred steps to a secret beach where we skim pebbles across the mirror-like lake. a sun-drenched hotel, a golden hour walk catching glimpses across the water, a cypress-lined odyssey, overhearing conversations while watching the sun set, lying on a dock as it bobs with the waves, watching the ducks as the sun paints the sky red before sinking beneath the mountains.

destinazione: varenna

2019

from one island to another

time flows differently under the sicilian sun

destinazione: ragusa

destinazione: ibla

abandoned industry / would-be roller coaster

destinazione: taormina

the city which clings to the side of a hill

2018

nel sud

the approach of summer called for one final trip down south; a week-long adventure with just one small backpack, travelling from place to place & meeting friends along the way. the goal was simple: eat as much good food as possible, soak up plenty of sun & sea, and appreciate every second of italian summer.

southern italy is a fantasy in which beach carnival meets ancient ruins. hot-tempered motorists zip through the same streets where children play. i kept expecting the vessuvio to blow at any second, bursting in the loud heat , covering the whole region in san marzano tomato sauce.

destinazione: ischia

destinazione: napoli

destinazione: sorrento

bagni della regina giovanna

destinazione: positano, amalfi coast

destinazione: roma

2018

train rides across northern italy

via lecco, 22, appartamento 2

catching the last metro home, tram parties, eating pizza on the floor while drinking wine, cremino ice cream at navigli, learning how to ride a bike while tipsy, 5pm spritz aperitivo, lying on the grass in the sun in sempione, eating chocolate doughnuts in the lidl parking lot with my favourite people, cutting my hair short, the sound of a trumpet & children playing streaming in through the open window.

origine: milano

spontaneous visits & waking up for coffee

an unheard exchange; that conversation must still be stored somewhere within those glowing walls

destinazione: torino

destinazione: verona

destinazione: bergamo

destinazione: portofino

walking to portofino along the coast

feels like a sacred pilgrimage

destinazione: sestri levante

destinazione: sirmione

swimming below the ancient ruins @ lago di garda

destinazione: lago di mergozzo

the lake under the hill

destinazione: cinque terre

solo hike between the towns of the cinque terre, the melody of an accordion floating on the breeze, stopping for a dip at every village

destinazione: venezia

4. ongoing travelogue

2024

following fairy trails

the land of rainbows, magical kingdoms & leprechauns sitting on bags of gold. a sojourn for the soul in dublin ended up feeling like home away from home

can you hear the trees whispering?

where the moss lives

into the woods we go

the language of hands

it’s always worth taking the scenic route

strangers i wish i knew

2023

on the edge of the atlantic

porto feels familiar somehow, like a dream you feel like you’ve already had only to realise you haven’t once you wake up

2022

a parisian getaway

a spontaneous trip to this magical city to fulfill all of our croissant & baguette dreams

2021

kragujevac

easa / serbia... finally together again; frolicking through fields full of wildflowers, embracing, meaningful conversations with new friends

2019

trpejca

incm / macedonia... like a migrating flock, we gathered in trpejca, a quiet lake-side community which we cohabited with its welcoming villagers

2019

lisboa

2019

villars-sur-ollons

easa tourist / switzerland; inalpe / désalpe

a staircase draped across the hills

2019

riga

one too many black balsams later in the deep, dark mid-winter

2018

croatia

re:easa in rijeka

2018

københavn

exploring botanical gardens, museums & planetariums, swinging in a hammock at the cherry blossom festival, being greeted by the smell of truffle at every corner, taking a wrong turn onto the bicycle snake bridge and flying over the city in our trusty box bike. copenhagen stole our hearts & filled our tummies.

2018

u-bahn state of mind

picture the urban mass that is berlin

bauhaus

2017

valencia

shot on disposable

5. commissions

2024

saviour or symptom

shoot for dezeen alongside text by ann dingli

full photo story published here

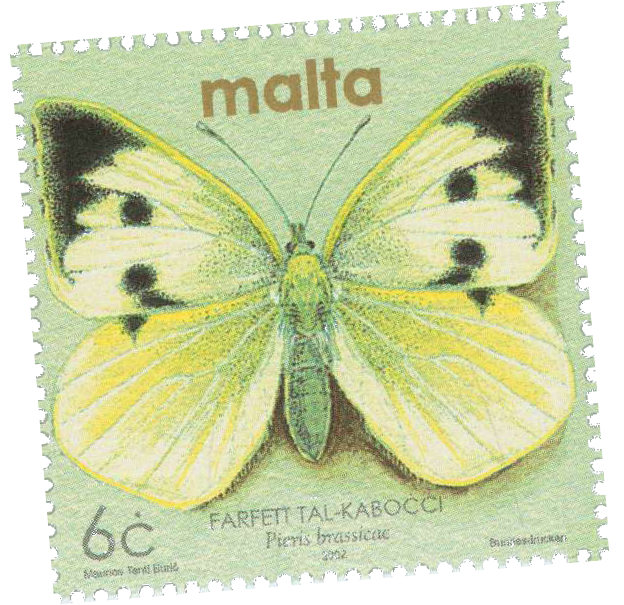

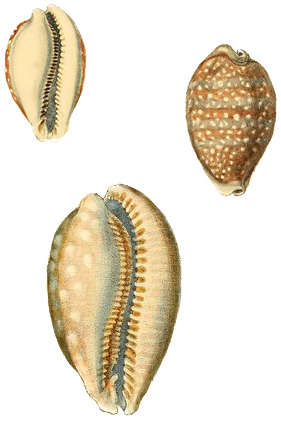

2024

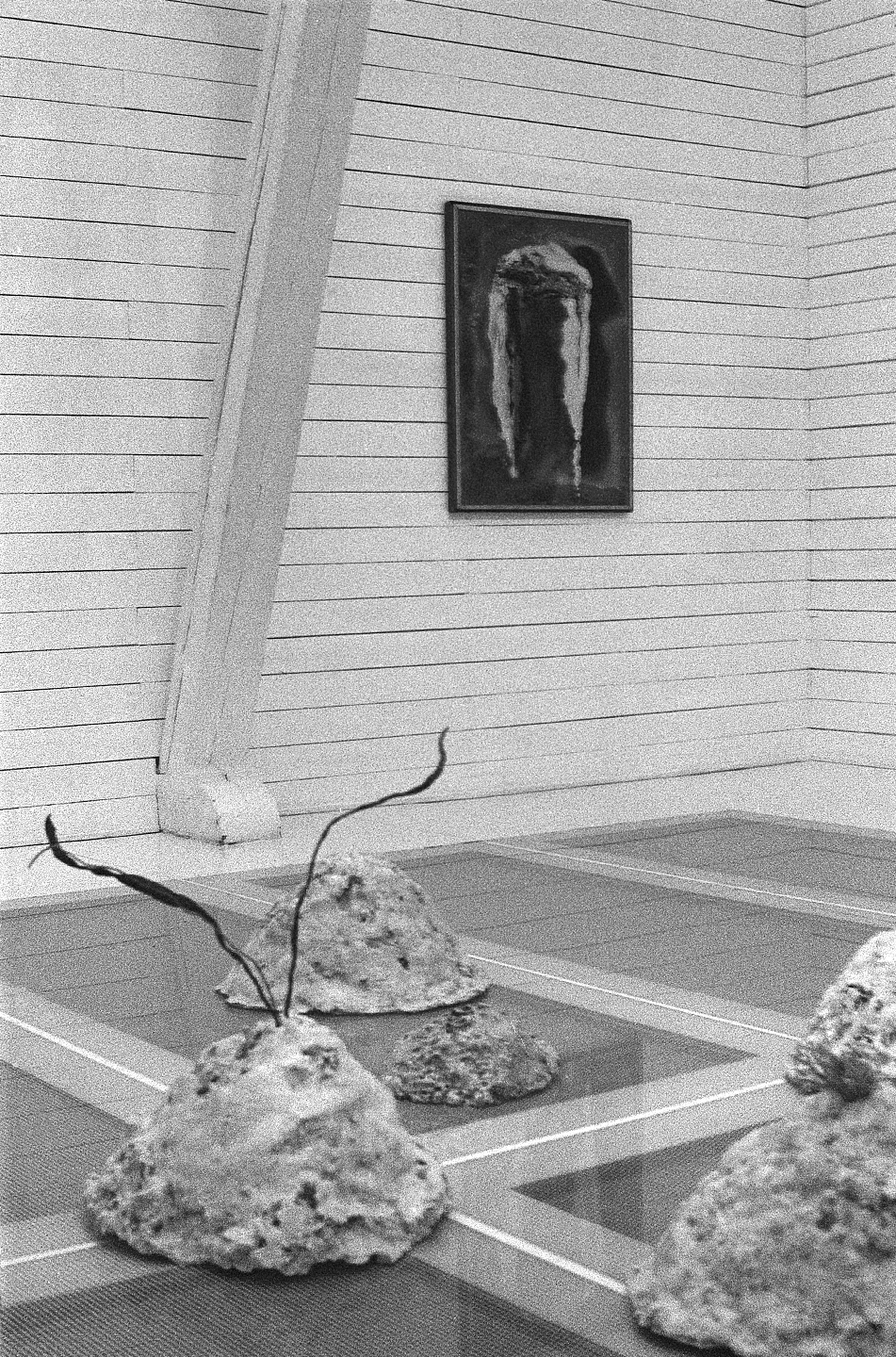

the myth of abundance

shoot for ap valletta at the design mt expo

the 'cabinet of curiosity' is used as a framework to explore the theme of water scarcity and artificial abundance in malta

collecting artefacts & specimens from around the maltese coastline

2024

she sells sea shells

shoot for amori mori

a mother-daughter team from spain crafting handmade jewellery pieces

2024

poolside shoot

shoot for da/da studio

2024

qolla / arzella / kresta

3d printed lamps inspired by coastal geological formations

commission for sforma studio by clara azzopardi

2024

an eternal holiday

handmade ceramics from portugal

commission for motel a miio

2024

trails in gold

jewellery inspired by island-life

commission for swedish jewellery brand bon isla

trails in gold i

trails in gold ii

honey-drizzled gold

nodes on a reed like rings on a finger

2024

of places yet to be

casa fortuna & its becoming

commission for daniel xuereb

portrait of a house & the person behind it

“

O Fortuna,like the moon

you are changeable,

ever waxing,

ever waning,

hateful life

first oppresses

and then soothes

as fancy takes it;

poverty

and power

it melts them like ice

”

- from the Carmina Burana, 13th century

2022

of places lost & imagined

id-dar ta’ mary vella & the stories interwoven within it

commission for luke dimech

“When you turn and look back down the years, you glimpse the ghosts of other lives you might have led; all houses are haunted.”

- Mantel, 2003

“

Every so often, if we’re lucky, we are struck with what Virginia Woolf called ‘moments of being’. I say ‘we are struck with’ as opposed to ‘we come across’ because that’s what it feels like, or rather, that’s what it has felt like to me. Not quite a slap in the face, nor some divine revelation. You are suddenly faced with a reality that seems almost new, though in the light of that newness everything seems realer and clearer than ever. Who you are. Where you are. Who you are with.

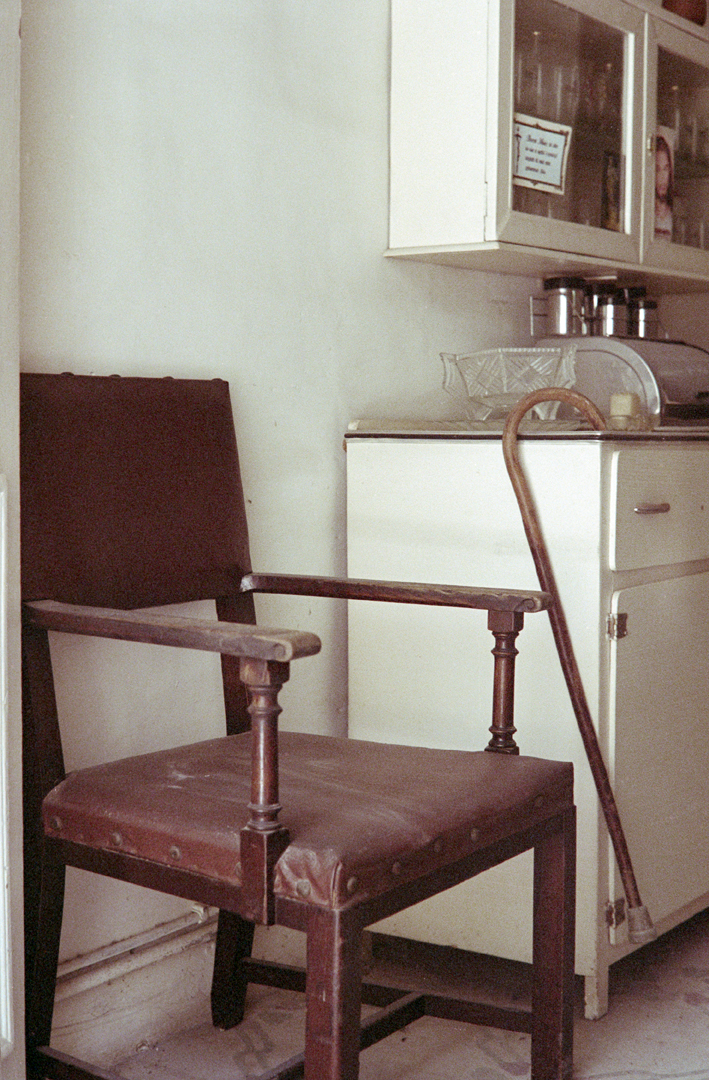

This house, this space that was occupied by my family for decades struck similarly every time I stepped into it. This house was, IS, central to my existence. I feel that everything I am has only been made real through this house. Every single person that has occupied it - the people born, the people that passed on, the people cared for, the meals cooked and eaten around the tables, the oranges picked peeled and savoured, the jokes told and laughs had. The chairs so worn in by the weighty bodies that claimed them they’re dented. Their seats now leather craters made by great buttocks… great-grandparent buttocks. This house, which I’ve always known as Aunty Mary’s house, is a moment of being in itself, this house makes us all real. This is where my grandmother grew up, this is where my father spent a fair deal of his childhood. This is from where we’ve inherited our sense of humours, our love of food, our appreciation for gathering around a table and being together as a family.

But any moment is fleeting, every moment has an end. And unfortunately this one is nearing its end, at least in the physical realm. This moment of my family’s life shall live on in our memories and in our blood. It is part of our inheritance for many more decades to come. Ths is a testament to what the house was and what it meant to us, but also to the lives that filled it and the purpose it served.

‘Id-dar ta’ Aunty Mary’ is still standing, though not for much longer. I will forever be grateful to have been one of the many to haunt its rooms, even if for a brief moment of being.

But any moment is fleeting, every moment has an end. And unfortunately this one is nearing its end, at least in the physical realm. This moment of my family’s life shall live on in our memories and in our blood. It is part of our inheritance for many more decades to come. Ths is a testament to what the house was and what it meant to us, but also to the lives that filled it and the purpose it served.

‘Id-dar ta’ Aunty Mary’ is still standing, though not for much longer. I will forever be grateful to have been one of the many to haunt its rooms, even if for a brief moment of being.

”

- words by luke dimech

mary’s spot when peeling & savouring oranges after picking them fresh from the garden

uncle victor’s spot & grandmother’s spot

“my dad tells stories of playing at this water pump as a child”

fresh from the garden

layers of a house

locking up